Tuesday, May 31, 2005

Critical mass

According to Scott Timberg's gloom-and-doom piece in the L.A. Times, traditional arts criticism is now going the way of the spinning jenny. There's some disagreement as to the pernicious impact of the Web: the excellent Alex Ross, whose blog recently featured a picture of his kitty, argues that the tug-of-war between print and pixels is not in fact a zero-sum game. "It's a way to refashion the art form," he insists, "from hopelessly anachronistic to a thriving, tech-savvy form." Dave Hickey is less sanguine about the state of affairs. "I do think that we're over," he says, making this hopelessly anachronistic critic tremble in his Bass loafers. "Being an art critic was one of those jobs like nighttime disk jockey or sewing machine repairman: It was a one- or two-generation job." He adds: "I'm like Wolfman Jack. The times have passed me by." Me, I'm not so nostalgic about the old days, when nitpicking titans walked the earth. At one point Timberg notes that latter-day critics "often pine for the 1940s and '50s, what the poet-critic Randall Jarrell called the 'age of criticism.'" But when Jarrell used that phrase, he didn't necessarily mean it as a compliment. Allow me to quote from the essay of the same name:

...a great deal of this criticism might just as well have been written by a syndicate of encyclopedias for an audience of International Business Machines. It is not only bad or mediocre, it is dull; it is, often, an astonishingly graceless, joyless, humorless, long-winded, niggling, blinkered, methodical, self-important, cliché-ridden, prestige-obsessed, almost-autonomous criticism.So much for the Golden Age. I suppose what I'm saying is that every era gets the criticism it deserves, and I don't think it's so terrible to have a babel of contentious voices in print and on the Web rather than a papal bull from Addison DeWitt.

Bad blood, translation panel, The Wounded Surgeon

I celebrated Memorial Day by hanging around the apartment in my bathrobe, reading an old New Yorker I found under the sofa cushion (which made me very skeptical about Mike Bloomberg's West Side stadium boondoggle: the floor and ceiling alone are supposed to run the taxpayers $600 million.) By the late afternoon my mood was ugly. But now I'm back, firing on all pistons, and the first thing that caught my attention was this fraternal spat, brought to you live from the Hay-on-Wye festival. Turns out that Christoper and Peter Hitchens have been giving each other the silent treatment for nearly four years, ever since P suggested that C was a Stalinist in the British papers. Not so! argues C. Despite some delicate therapeutic maneuvering on the part of the moderator, the brothers don't really kiss and make up--in fact they have to be bullied into actually looking each other in the eye at the end of the exchange. But the report does include this priceless bit of audience participation:

Meanwhile, in The New York Sun, Gary Shapiro offers some extended coverage of last week's translation panel at Housing Works. The nattily attired reporter (who no longer wears that porkpie hat with a business card stapled to the brim) clearly took better notes than I did. There's much more info on the fiscal realities of literary translation. There's also a bonus quip from Dennis Loy Johnson, who responded to questions about how a small publisher could make up for the whole, revenue-slaying enterprise by revealing yet another of his cottage industries: "We’re selling cupcakes outside."

Finally: I picked up Adam Kirsch's The Wounded Surgeon, which had been sitting on the floor of my office for the past two weeks. My inspiration, I freely admit, was the poke in the eye David Lehman gave the author in this week's New York Times Book Review. Having enjoyed some of Kirsch's essays, I couldn't believe the book could be quite that bad. Well, it is...problematic. And as Lehman suggests, the real flaw is Kirsch's thesis, which deploys not just a straw man but a platoon of straw men--enough for an entire haystack. Kirsch's argument: despite the "confessional" label, Lowell, Berryman, and Plath never treated poetry as a glorified Dictaphone, never transcribed their experiences directly into verse. The problem is that nobody really believes this in the first place. Nor does the opposite, New Critical assertion--that the poems are hermetically sealed off from the life--hold water. Caught between these absurdities, Kirsch trots out T.S. Eliot's tired riffs on impersonality and the objective correlative. Are we really going to pretend that "Skunk Hour" or The Dream Songs represent "an escape," as Eliot put it, "from personality"? Get out of town! As for the porous membrane between life and art, let Lowell speak for himself, in his letter of July 2, 1976 to Elizabeth Hardwick, where he discusses his Selected Poems:

Female audience member: Excuse me. I'm not usually awkward at all but I'm sitting here and we're asked not to smoke. And I don't like being in a room where smoking is going on.

CH (smoking heavily): Well, you don't have to stay, do you darling. I'm working here and I'm your guest. OK. This is what I like.

IK: Would you just stub that one out?

CH: No. I cleared it with the festival a long time ago. They let me do it. If anyone doesn't like it they can kiss my ass.

Meanwhile, in The New York Sun, Gary Shapiro offers some extended coverage of last week's translation panel at Housing Works. The nattily attired reporter (who no longer wears that porkpie hat with a business card stapled to the brim) clearly took better notes than I did. There's much more info on the fiscal realities of literary translation. There's also a bonus quip from Dennis Loy Johnson, who responded to questions about how a small publisher could make up for the whole, revenue-slaying enterprise by revealing yet another of his cottage industries: "We’re selling cupcakes outside."

Finally: I picked up Adam Kirsch's The Wounded Surgeon, which had been sitting on the floor of my office for the past two weeks. My inspiration, I freely admit, was the poke in the eye David Lehman gave the author in this week's New York Times Book Review. Having enjoyed some of Kirsch's essays, I couldn't believe the book could be quite that bad. Well, it is...problematic. And as Lehman suggests, the real flaw is Kirsch's thesis, which deploys not just a straw man but a platoon of straw men--enough for an entire haystack. Kirsch's argument: despite the "confessional" label, Lowell, Berryman, and Plath never treated poetry as a glorified Dictaphone, never transcribed their experiences directly into verse. The problem is that nobody really believes this in the first place. Nor does the opposite, New Critical assertion--that the poems are hermetically sealed off from the life--hold water. Caught between these absurdities, Kirsch trots out T.S. Eliot's tired riffs on impersonality and the objective correlative. Are we really going to pretend that "Skunk Hour" or The Dream Songs represent "an escape," as Eliot put it, "from personality"? Get out of town! As for the porous membrane between life and art, let Lowell speak for himself, in his letter of July 2, 1976 to Elizabeth Hardwick, where he discusses his Selected Poems:

Autobiography predominates, almost forty years of it. And now more journey of the soul in my new book. I feel I, or someone, wrote everything beforehand. If I had read it at twenty would I have been surprised, would I have dared go on?When Kirsch isn't grinding his anti-confessional axe, he makes some intelligent points about Lowell, Bishop, and Randall Jarrell (he's especially perceptive about the repressed current of sexuality in Jarrell's best work.) It's too bad the book itself comes off as such a rear-guard action.

Friday, May 27, 2005

Today's worst mixed metaphor (as of 3:38 PM), plus cursing

First, let me make one thing clear: I'm not a puritan about these matters. I'm all for the promiscuous mingling of metaphoric parts. But when you cram too many into a small space, the result is unintentional levity. My specimen for today comes from Michiko Kakutani's review of Sean Wilsey's Oh The Glory of It All (via Bookslut):

Over at the Literary Saloon I found this link to an excellent article about how to translate cursing. The translators had chosen to scale one of the great Alps of potty-mouthed lit: Irvine Welsh's Trainspotting. In the short passage under consideration, the linguistic leitmotifs are cunt (31 times!) and fuck (42 times!!). And to make matters even trickier, the target language happens to be joual, a vernacular French dialect used in Montreal. The solutions are ingenious: Wajdi Mouawad and Martin Bowman drew on the dialect's rich assortment of blaspheming religous epithets. For cunt they use câlisse, meaning "chalice," and they also throw in a bunch of tabarnak ("tabernacle") and Hostie ("Host"), which is presumably enough to make a joual-speaking matron blush to a deep beet-red. Having faced some of these knotty problems myself--how to render Oriana Fallaci's cazzo d'un cazzo stracazzato, a priapic formulation the author claimed to have made up herself?--I tip my hat to Mouawad and Bowman both. They are brave men.

It's a sprawling kitchen sink of a memoir, stuffed to the gills with seemingly everything the author can remember about his youth and in dire need of some industrial-strength editing, but at the same time, an epic performance: by turns heartfelt, absurd, self-indulgent, self-abasing, silly and genuinely moving.I'm not taking her to task for the shopworn figures of speech--kitchen sink, stuffed to the gills, industrial-strength--having used them all myself, many times. But by crowding them together, she forces the reader to ask: can a kitchen sink have gills? A distracting question. As for the Wilsey, the excerpt in the New Yorker made me want to run in the opposite direction--I felt like I was being hosed down with charm and whimsy--but I suppose I should give it another chance.

Over at the Literary Saloon I found this link to an excellent article about how to translate cursing. The translators had chosen to scale one of the great Alps of potty-mouthed lit: Irvine Welsh's Trainspotting. In the short passage under consideration, the linguistic leitmotifs are cunt (31 times!) and fuck (42 times!!). And to make matters even trickier, the target language happens to be joual, a vernacular French dialect used in Montreal. The solutions are ingenious: Wajdi Mouawad and Martin Bowman drew on the dialect's rich assortment of blaspheming religous epithets. For cunt they use câlisse, meaning "chalice," and they also throw in a bunch of tabarnak ("tabernacle") and Hostie ("Host"), which is presumably enough to make a joual-speaking matron blush to a deep beet-red. Having faced some of these knotty problems myself--how to render Oriana Fallaci's cazzo d'un cazzo stracazzato, a priapic formulation the author claimed to have made up herself?--I tip my hat to Mouawad and Bowman both. They are brave men.

Thursday, May 26, 2005

The sue me, sue you blues

Back in April 2004, Adel Smith, the president of the Muslim Union of Italy, filed suit against Oriana Fallaci. He argued that her latest book, The Force of Reason, amounted to a hateful and defamatory attack on Islam and its adherents. Now (according to the BBC News) the suit has come within hailing distance of an actual courtroom. The preliminary investigative judge Armando Grasso has given the prosecution ten days to formulate its charges, and noted that the book does indeed contain expressions "unequivocally offensive to Islam." Fallaci and her attorneys, who have already beat back a legal assault on The Rage and the Pride in the French courts, are no doubt preparing a free speech defense. My assumption is that the author will prevail should the case go to trial--but given the kinks and contortions of the Italian judicial system, who knows?

Having had my own Close Encounter of the Worst Kind with Fallaci back in the early 1990s--I translated Inshallah, a miserable and acrimonious experience--I'm finding it hard to be objective here. I haven't read The Force of Reason, which will be published in this country on August 23. I did thumb through The Rage and the Pride, which looked like a real mess to me: an incoherent argument delivered in the author's own, Chico-Marx-like brand of broken English. (Don't take my word for it, though: see how the anti-Islamist Christopher Hitchens spit-roasted this rambling production in The Atlantic Monthly, calling it "a sort of primer in how not to write about Islam.") If the new book is anything like its predecessor, I'm not sure how useful an addition it will be to the debate about Islam and the West. Yet I will defend Oriana's absolute right to express her ungrammatical rage, as long as I don't have to read it. Whether Armando Grasso will take a similar tack is anybody's guess.

Having had my own Close Encounter of the Worst Kind with Fallaci back in the early 1990s--I translated Inshallah, a miserable and acrimonious experience--I'm finding it hard to be objective here. I haven't read The Force of Reason, which will be published in this country on August 23. I did thumb through The Rage and the Pride, which looked like a real mess to me: an incoherent argument delivered in the author's own, Chico-Marx-like brand of broken English. (Don't take my word for it, though: see how the anti-Islamist Christopher Hitchens spit-roasted this rambling production in The Atlantic Monthly, calling it "a sort of primer in how not to write about Islam.") If the new book is anything like its predecessor, I'm not sure how useful an addition it will be to the debate about Islam and the West. Yet I will defend Oriana's absolute right to express her ungrammatical rage, as long as I don't have to read it. Whether Armando Grasso will take a similar tack is anybody's guess.

Wednesday, May 25, 2005

Lowell, Brodsky, Tillman & Co.

Just a few notes. First: Christmas came early this year--meaning that I got a copy of The Letters of Robert Lowell in the mail. The book, which weighs in at a strapping 852 pages, is clearly going to be a joy. It also reveals a much more spontaneous, attractively slapdash writer. Lowell, after all, was an obsessive reviser of his poetry, and one reason he abandoned the autobiographical prose excursion he began with "Antebellum Boston" and "91 Revere Street" was that there were too many damn words to change, fix, fiddle with. But correspondence liberated him from this need to play snooker with every single syllable. They're marvelous, sly, illuminating letters, from the very first (written by a 19-year-old college student to Ezra Pound) to the very last (a note to Caroline Blackwood about their son Sheridan, who "(wisely) preferred people to swans and a rubber-tyre swing to people.")

Next: according to a piece in the St. Petersburg Times (via Bookslut), there's a plan afoot to transform Joseph Brodsky's diminutive boyhood apartment into a museum. The problem is that the current tenants are reluctant to leave. A mother and daughter in one room fear that they won't be able to find other lodgings. And the guy living in Brodsky's old bedroom--a twelve-meter-square cubbyhole!--is behaving "as if he had struck oil," says Alexander Kobak, a member of the St. Petersburg City Hall's Cultural Heritage Council. We're talking about the same apartment Brodsky described in his classic essay "In a Room and a Half" (reprinted in Less Than One), and this sentence makes me hope they'll eventually find the funds to restore the sanitary facilities as well: "As for the bathroom, Russian hygienic habits are such that eleven people would seldom overlap when either taking a bath or doing their basic laundry. The latter hung in two long corridors that connected the rooms to the kitchen, and one knew the underwear of one's neighbors by heart."

Finally, I got one of those funny pangs the other day when you simply must hear a specific song, so I hastened to the iTunes store and put my 99 cents on the barrelhead for Floyd Tillman's "This Cold War With You." I've always loved the lugubrious melody and the Eisenhower-era conceit of the lyrics:

Next: according to a piece in the St. Petersburg Times (via Bookslut), there's a plan afoot to transform Joseph Brodsky's diminutive boyhood apartment into a museum. The problem is that the current tenants are reluctant to leave. A mother and daughter in one room fear that they won't be able to find other lodgings. And the guy living in Brodsky's old bedroom--a twelve-meter-square cubbyhole!--is behaving "as if he had struck oil," says Alexander Kobak, a member of the St. Petersburg City Hall's Cultural Heritage Council. We're talking about the same apartment Brodsky described in his classic essay "In a Room and a Half" (reprinted in Less Than One), and this sentence makes me hope they'll eventually find the funds to restore the sanitary facilities as well: "As for the bathroom, Russian hygienic habits are such that eleven people would seldom overlap when either taking a bath or doing their basic laundry. The latter hung in two long corridors that connected the rooms to the kitchen, and one knew the underwear of one's neighbors by heart."

Finally, I got one of those funny pangs the other day when you simply must hear a specific song, so I hastened to the iTunes store and put my 99 cents on the barrelhead for Floyd Tillman's "This Cold War With You." I've always loved the lugubrious melody and the Eisenhower-era conceit of the lyrics:

The sun goes down and leaves me sad and blue.

The Iron Curtain falls on this Cold War with you.

Tuesday, May 24, 2005

Foreign exchange

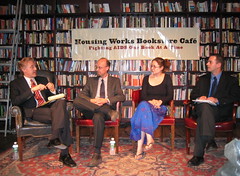

Let's start with the bad news. Out of 195,000 books published in America last year, a whopping 864 were translated works of fiction. Now for worse news: it's not getting any better, or easier. Or so one might conclude from last night's panel discussion at Housing Works, which featured Dennis Loy Johnson (of the Moby Lives/Melville House multimedia empire), Michael Orthofer (of The Literary Saloon), Margarrita Shalina (a fiction buyer for Manhattan's St. Mark's Bookshop), and Chad Post (of Dalkey Archive Press). Looking unnaturally luminous under the C-SPAN klieg lights, the panelists ran through a litany of obstacles to publishing foreign books in this country.

First: we're in a rather xenophobic moment. Much of the media--hey, much of the populace--would sooner spend a holiday weekend at Guantánamo Bay than celebrate a non-American author. According to Johnson, one television producer pulled a last-minute cancellation on Bernard-Henri Lévy simply because the guy is French. ("No accents allowed," was the curt explanation.) Johnson also noted that he's been pressured to remove the translator's name from the jackets of Melville House titles, in order to fool consumers into thinking the books were written in English.

Even in a more hospitable cultural climate, however, the financial hurdles would still be daunting. As Post explained, a translated work typically runs Dalkey in the neighborhood of $35,000 to produce. In return they can hope to sell between 900 and 1,500 copies of the book. "Two thousand copies is a success," Post said. "Three thousand is a wild success." These are not numbers to warm a trade publisher's heart. Dalkey, of course, is a nonprofit, which can stanch its losses by grants and fundraising. But Melville House is a for-profit operation ("Or so they tell me," Johnson joked), meaning that it must eke out some kind of margin to survive.

Orthofer, whose beard and spectacles make him resemble a kinder, gentler, more studious Trotskyite, argued that the best way to boost translation is to build demand: "The real challenge is getting the word out." Few people are doing so as diligently as Orthofer himself at the Literary Saloon, and Shalina delivered the heartening news that his efforts have moved at least a trickle of customers into St. Mark's to purchase translated works. She also defended the presence of cheaper, out-of-copyright translations of older classics. Sure, she argued, we need elegant new versions of Tolstoy and Gogol and Dostoevsky. But she put in a plug for the frumpier, turn-of-the century texts we all read in high school: "Let's not kick around poor Constance Garnett!"

By now it was question-and-answer time, and much of the audience seemed to be in a depressed stupor. "Is there any good news?" somebody asked (okay, it was me.) And yes, the panel responded, there were some glimmers of hope, starting with the enormous success of the PEN World Voices Festival. Post and Shalina went on to discuss the current Reading the World project--a marketing initiative involving five prominent publishers of translated works and 100 independent bookstores around the country. To sum up: All is not lost! Publishing foreign books is no mere exercise in masochism! And as long as there's some appetite for reading--which Shalina defined as "a deviant act"--there will be an appetite for reading works in translation.

First: we're in a rather xenophobic moment. Much of the media--hey, much of the populace--would sooner spend a holiday weekend at Guantánamo Bay than celebrate a non-American author. According to Johnson, one television producer pulled a last-minute cancellation on Bernard-Henri Lévy simply because the guy is French. ("No accents allowed," was the curt explanation.) Johnson also noted that he's been pressured to remove the translator's name from the jackets of Melville House titles, in order to fool consumers into thinking the books were written in English.

Even in a more hospitable cultural climate, however, the financial hurdles would still be daunting. As Post explained, a translated work typically runs Dalkey in the neighborhood of $35,000 to produce. In return they can hope to sell between 900 and 1,500 copies of the book. "Two thousand copies is a success," Post said. "Three thousand is a wild success." These are not numbers to warm a trade publisher's heart. Dalkey, of course, is a nonprofit, which can stanch its losses by grants and fundraising. But Melville House is a for-profit operation ("Or so they tell me," Johnson joked), meaning that it must eke out some kind of margin to survive.

Orthofer, whose beard and spectacles make him resemble a kinder, gentler, more studious Trotskyite, argued that the best way to boost translation is to build demand: "The real challenge is getting the word out." Few people are doing so as diligently as Orthofer himself at the Literary Saloon, and Shalina delivered the heartening news that his efforts have moved at least a trickle of customers into St. Mark's to purchase translated works. She also defended the presence of cheaper, out-of-copyright translations of older classics. Sure, she argued, we need elegant new versions of Tolstoy and Gogol and Dostoevsky. But she put in a plug for the frumpier, turn-of-the century texts we all read in high school: "Let's not kick around poor Constance Garnett!"

By now it was question-and-answer time, and much of the audience seemed to be in a depressed stupor. "Is there any good news?" somebody asked (okay, it was me.) And yes, the panel responded, there were some glimmers of hope, starting with the enormous success of the PEN World Voices Festival. Post and Shalina went on to discuss the current Reading the World project--a marketing initiative involving five prominent publishers of translated works and 100 independent bookstores around the country. To sum up: All is not lost! Publishing foreign books is no mere exercise in masochism! And as long as there's some appetite for reading--which Shalina defined as "a deviant act"--there will be an appetite for reading works in translation.

Sunday, May 22, 2005

Dennis the Menace in America

Inside every fat novel is a thin movie, wildly signaling to be let out. Or so I thought when I read (at Monsters and Critics) about Jerzy Skolimowski's $19 million adaptation of In America. The late Susan Sontag's final work of fiction is something of a strange choice for the big screen. Why? Because although the story revolves around an actress--the Polish diva Maryna Zalezowska, who founds a failed utopian commune in California and then rises from the ashes to become the J. Lo of the Gilded Age--the book itself is very interior and anti-dramatic. There are long stretches of gorgeous, almost hallucinatory exposition, an occasional dab of sex, but no car chases that I can recall. I assume that the plot will be neatly filleted for the film (which has been economically retitled America.) Skolimowski may do a great job. He's Polish, after all, and to judge from Moonlighting, he has a gift for sneaky, comical concision. Isabelle Huppert sounds just right for Maryna. What wigged me out, though, was the news that Dennis Hopper will "star" as the manager who revives the diva's career. Maryna was unquestionably the star of the novel--the other characters were doing cameos, more or less. What will happen when a drawling, pop-eyed psycho assumes center stage? And can't they find a part for Topher Grace in there?

Friday, May 20, 2005

A musical offering

I've been reading a galley of Studs Terkel's And They All Sang: Adventures of an Eclectic Disk Jockey, which is enormous fun. Terkel is probably one of the only human beings to interview both Louis Armstrong (in 1962) and Henry Threadgill (in 1988), but the focus is by no means confined to jazz. He trades conversational fours with the likes of Andrés Segovia, Thomas A. Dorsey, Alfred Brendel, Janis Joplin, Birgit Nilsson, Big Bill Broonzy, Aaron Copland, Ravi Shankar, and (last but not least) a wet-behind-the-ears Bob Dylan, who shares this classified info about his nicotine habit: "I started smoking at eleven years old, I stopped once to catch my breath." Other highlights: when Leonard Bernstein starts to discuss the glories of Marc Blitzstein's 1937 musical The Cradle Will Rock, Studs simply notes that he was in it. Also, the exchange with Virgil Thomson is a keeper. One example, on the perils of modern technology circa 1965: "Grandeur requires limitations. It's pretty hard to write something grand, which is inevitably going to be performed though one small loudspeaker about fifteen inches across. That circumstance itself is not exactly the entire Michigan lakefront, mobilized for a Fourth of July." (Full disclosure: And They All Sang is published by The New Press, which also published Amazonia, but I would have relished this book if it had been hand-cranked off a mimeograph machine.)

Specimen Days, Ozick, plus a soupcon of Idol

I have fallen down on my blogging duties over the past few days. Partly out of inertia, partly because I had a house guest--my friend Dave, the one who's such a big Carrie Underwood fan and who expressed not a whit of surprise when Vonzell was kicked to the curb during the last show. Baby V, we hardly knew ye, etc etc. Anyway, I followed through on my earlier threat and have been reading Walt Whitman's Specimen Days (in the handsome, Smyth-sewn, decay-proof edition from the Library of America.) It's an autobiographical miscellaney, which begins with some notes about the poet's ancestry and then cuts straight to the chase: Whitman's service as a kind of sublime Candy Striper during the Civil War. He later called himself a "wound dresser," but that's a metaphorical description at best. What he did was sit by the bedside of the Union wounded and offer comfort, conversation, oranges, tobacco, stamps. On one occasion--to celebrate the victory at Gettysburg--he procured "several bottles of blackberry and cherry syrup, good and strong," and served iced beverages throughout the wards. If I seem to be making light of his efforts, I'm not. The consolations he offered were real, and desperately needed. And his account is fascinating: very factual, clear-eyed, with only an occasional passage of Whitmanian music. In one incredible bit, he notes that the United States Patent Office had been converted into a military hospital. Several of the wards are filled with

Over at Literary Saloon, I read this snippet from Theo Tait's review of Cynthia Ozick's latest (in the London Review of Books):

high and ponderous glass cases, crowded with models in miniature of every kind of utensil, machine or invention, it ever enter'd into the mind of man to conceive; and with curiosities and foreign presents. Between these cases are lateral openings, perhaps eight feet wide and quite deep, and in these were placed the sick, with a long double row of them up and down through the middle of the hall. Many of them were very bad cases, wounds and amputations.Whitman sees himself as a reporter in this case, and doesn't dwell on a signal irony: the mutilated victims of the first modern, mass-production war expiring in a virtual Temple of Industrial Progress. (Footnote on a footnote: towards the end, the poet shares some of his discarded titles for Specimen Days. My two favorites are Notes of a half-Paralytic and Only Mulleins and Bumble-Bees, but they're all pretty great.)

Over at Literary Saloon, I read this snippet from Theo Tait's review of Cynthia Ozick's latest (in the London Review of Books):

It is sometimes seen as surprising that she is so little read in Britain. Her formidable essays have been published and admired here; but, of her nine works of fiction, only The Bear Boy--published in America as Heir to the Glimmering World--is currently in print. There is, emphatically, no great mystery about this: I would bet good money that she has not been much read in America either, outside the band of academics often described as "the Ozick industry."A losing bet, that one. I share Michael Orthofer's lifted eyebrow at the very idea of an "Ozick industry." But I would also like to take issue with the image of Cynthia Ozick as the Little Match Girl of American Letters. She is not an obscurity. Her criticism has perhaps been more celebrated than her fiction. But she also happens to be the author of The Shawl, which pops up in numerous anthologies and college curricula, and she doesn't occupy the same out-of-print limbo here that she does in Britain. (Another footnote: Ozick has some severe doubts about Holocaust lit in general and The Shawl in particular, which she voiced in this 2000 interview I did for Amazon.)

Wednesday, May 18, 2005

Brief Encounter: Alix Ohlin

From time to time House of Mirth will feature Brief Encounters--which is to say, concise exchanges with authors, editors, translators, poets, critics, and various other high-wattage luminaries. The series commences with Alix Ohlin, whose novel The Missing Person was published by Knopf earlier this month. (You can read my review from the Los Angeles Times Book Review here.)

James Marcus: Could you say a few words about how the various strands of the novel--the AWOL brother, the Earth-First-like campaign, the enigmatic paintings, and the various familial fissures--came together? Did you start with one, or juggle them simultaneously?

Alix Ohlin: I started with the main character, Lynn, and her story--which is really the story of an adult child coming to see her parents as real people, with flaws and virtues and complex histories, rather than as idealized (or demonized) versions of herself. Then I started to think about environmental issues, and I realized that there we have a similar idea on a much larger scale--we have to grapple with the actions, however flawed, of previous generations, and their ecological effects on the earth. So I decided there could be two plots that ultimately would play off each other in interesting ways. Wylie, the AWOL brother, is the connective tissue between the different worlds in the book, and the paintings are a way of providing tangible mystery between Lynn and her dead father.

That was my original idea, but I'm not sure how much it's there in the final version. The finished book turns out to be more about dealing with loss and change--though still on the two levels, within the family and in the landscape.

Marcus: Your parched and panoramic portrait of Albuquerque is one of the best things about the book. Have you spent much time out there? In any case, why did you decide to set the story there?

Ohlin: I grew up in Canada, but my mother is from New Mexico, and in the summer time we would often drive four or five days across the US (with no air conditioning!) to visit my grandparents, who lived in New Mexico. It was such a fascinating place, so different from where I was growing up. After college I moved to Albuquerque and I lived there for four years, working at various odd jobs and writing bad, sensitive short stories that never got published. I set the book in Albuquerque as a way of remembering that time to myself, and the city really did take over the book. I had no idea, when I started, how much a presence the place would have.

Marcus: The more your protagonist Lynn learns, the less she knows. Or to use your more elegant formulation: "The world was densely populated with things I did not know." Does this situation change in any fundamental way by the end of the novel?

Ohlin: I don't think so. I think that's kind of the point. Lynn starts the book out as a bit of a shallow know-it-all; she's very brittle and judgmental and thinks she knows more than her brother and her mother about the way things are--both in their family and in life. The events of the summer that are recounted in the book prove how wrong she is. For her, to grow up is to learn how much she doesn't know, and to accept it with some humility.

Marcus: You're very canny about the "elaborate diplomacy" of family life. But does Lynn's family strike you as typical in its many-splendored dysfunction?

Ohlin: I guess some of it is a little exaggerated for comic effect. But other parts of it I think are true in lots of families--especially the way that Lynn and Wylie, the siblings, are alternately vying for the titles of good child and black sheep. And the way that both of them, along with their mother, are constantly feeling misunderstood by one another--and yet craving that understanding so much. The elaborate diplomacy that keeps them acting nice to each other over dinner isn't just about refusing to acknowledge their conflicts, in my opinion. It has to do with the fact that they also love each other and want to be a perfect family, even as they are realizing every second how totally imperfect their relationships with one another are.

Marcus: Finally: what are you working on now?

Ohlin: I'm working on a collection of short stories, which will also be published by Knopf, sometime in the next couple of years. I've also just started a new novel, but it's really just the germ of an idea right now. It has no eco-terrorists in it, and no desert landscape--that's about all I know so far.

James Marcus: Could you say a few words about how the various strands of the novel--the AWOL brother, the Earth-First-like campaign, the enigmatic paintings, and the various familial fissures--came together? Did you start with one, or juggle them simultaneously?

Alix Ohlin: I started with the main character, Lynn, and her story--which is really the story of an adult child coming to see her parents as real people, with flaws and virtues and complex histories, rather than as idealized (or demonized) versions of herself. Then I started to think about environmental issues, and I realized that there we have a similar idea on a much larger scale--we have to grapple with the actions, however flawed, of previous generations, and their ecological effects on the earth. So I decided there could be two plots that ultimately would play off each other in interesting ways. Wylie, the AWOL brother, is the connective tissue between the different worlds in the book, and the paintings are a way of providing tangible mystery between Lynn and her dead father.

That was my original idea, but I'm not sure how much it's there in the final version. The finished book turns out to be more about dealing with loss and change--though still on the two levels, within the family and in the landscape.

Marcus: Your parched and panoramic portrait of Albuquerque is one of the best things about the book. Have you spent much time out there? In any case, why did you decide to set the story there?

Ohlin: I grew up in Canada, but my mother is from New Mexico, and in the summer time we would often drive four or five days across the US (with no air conditioning!) to visit my grandparents, who lived in New Mexico. It was such a fascinating place, so different from where I was growing up. After college I moved to Albuquerque and I lived there for four years, working at various odd jobs and writing bad, sensitive short stories that never got published. I set the book in Albuquerque as a way of remembering that time to myself, and the city really did take over the book. I had no idea, when I started, how much a presence the place would have.

Marcus: The more your protagonist Lynn learns, the less she knows. Or to use your more elegant formulation: "The world was densely populated with things I did not know." Does this situation change in any fundamental way by the end of the novel?

Ohlin: I don't think so. I think that's kind of the point. Lynn starts the book out as a bit of a shallow know-it-all; she's very brittle and judgmental and thinks she knows more than her brother and her mother about the way things are--both in their family and in life. The events of the summer that are recounted in the book prove how wrong she is. For her, to grow up is to learn how much she doesn't know, and to accept it with some humility.

Marcus: You're very canny about the "elaborate diplomacy" of family life. But does Lynn's family strike you as typical in its many-splendored dysfunction?

Ohlin: I guess some of it is a little exaggerated for comic effect. But other parts of it I think are true in lots of families--especially the way that Lynn and Wylie, the siblings, are alternately vying for the titles of good child and black sheep. And the way that both of them, along with their mother, are constantly feeling misunderstood by one another--and yet craving that understanding so much. The elaborate diplomacy that keeps them acting nice to each other over dinner isn't just about refusing to acknowledge their conflicts, in my opinion. It has to do with the fact that they also love each other and want to be a perfect family, even as they are realizing every second how totally imperfect their relationships with one another are.

Marcus: Finally: what are you working on now?

Ohlin: I'm working on a collection of short stories, which will also be published by Knopf, sometime in the next couple of years. I've also just started a new novel, but it's really just the germ of an idea right now. It has no eco-terrorists in it, and no desert landscape--that's about all I know so far.

Monday, May 16, 2005

Some lines from Whitman

This weekend I was thumbing through An American Procession, Alfred Kazin's peppery and opinionated survey of American lit. The author makes no pretense of being Olympian in his judgments--he allots a chapter to Thoreau, for example, but it's clear that he considers him a self-indulgent pain in the ass. Anyway, the book is also jammed with thousands of great quotations, including this tremendous description of Abe Lincoln by Walt Whitman: "I think well of the President. He has a face like a Hoosier Michael Angelo, so awful ugly it becomes beautiful, with its strange mouth, its deep cut, criss-cross lines, and its doughnut complexion." That really made me want to read Whitman's prose book from the same period, Specimen Days. It also made me hungry for an old-fashioned plain and a cup of coffee.

Today's worst mixed metaphor (as of 8:42 AM)

I just finished reading David Carr's piece about Tina Brown in the New York Times. The author is a wee bit generous in his assessment of Topic A with Tina Brown--he mentions that the CNBC show typically drew a subpar audience of 62,000, but omits the widely reported fact that the most recent broadcast nailed a meager 4,000 viewers. (You could reach a similar audience by standing in Times Square with a megaphone. Maybe even without a megaphone.) But anyway, I'm not here to kick around Tina Brown. I wanted to note a wonderful bit of metaphor-mangling on the second page of the piece. Here we go:

Once, her magazines took readers inside the star chambers where the sausages were made. But audiences seem to have no interest in that: they just want the sausage, the rawer the better.I know what a star chamber is, and I know what a sausage is. Put them together and you get--confusion. Or some kind of judicially regulated kielbasa.

Friday, May 13, 2005

Look, Ma, no hands!

I watched Scott McClellan's briefing shortly after the Great Cessna Panic on Wednesday. At that point I found his vague harrumphing more forgivable--I figured it was still a fluid situation and he probably didn't have all the facts. But the subsequent revelation that President Bush was not informed of the whole crisis until after he finished his bucolic bicycle ride made me a little unhappy. And this Pirandellian dialogue between McClellan and the White House press corps (via Editor & Publisher) is absolutely mortifying. The best, which is to say the worst, exchange:

Q: Right, but there seems to be so many disconnects here. You've got a plane that was assessed as not being a threat, you've got 35,000 people evacuated, you've got a person who you claim is a hands-on commander in chief who is left to go ride his bicycle through the rural wildlands of Maryland while his wife is in some secure location somewhere, it's just not adding up.This kind of ducking and weaving amounts to a civic menace. Thomas Jefferson had it right: I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just.

McCLELLAN: Well, John, I disagree, and let me tell you why: You have highly skilled professionals who are involved in situations like this, in a variety of different fronts, from our Homeland Security officials to our National Security Council officials to our Secret Service officials and to others and to local officials, and they work very closely together. The protocols that were put in place were followed, and I think they were followed well.

Thursday, May 12, 2005

Mamet on Simon, Wolfe on bad-boy execs

It's too easy to make fun of the Huffington Post--like shooting guppies in a brandy snifter--so I'll cease and desist. I'll also acknowledge that I found two interesting items on the site today. First, David Mamet celebrates the defenestration of John Simon over at New York Magazine. Simon has always deplored the playwright's potty-mouthed vision of contemporary life, and yes, the feeling is mutual. Mamet's dispatch in its entirety reads: "I have just heard that John Simon has been fired from the post he long disgraced at New York Magazine. In his departure he accomplishes that which during his tenure eluded him: he has finally done something for the American Theatre." No mincing words there. But for a more positive spin on Simon's long tenure as the Grim Reaper of American Drama, see this post ("Off the aisle") from Terry Teachout.

The other link I found there, from the New Mexican, concerns Tom Wolfe's appearance at Brazil's Biennial Book Fair in Rio de Janeiro. First revelation: he's cut back from 34 white suits to a paltry, pauperistic 24. Next revelation: he's ditching fiction for his next book, which will focus on the shabby-chic impulses of executive types. Given Wolfe's keen eye for upper-middle-class pageantry, this sounds like fertile terrain. But oddly enough, he seems less interested in the nostalgie-de-la-boue angle, and more perplexed that America's most eligible bachelors are sending out mixed signals:

The other link I found there, from the New Mexican, concerns Tom Wolfe's appearance at Brazil's Biennial Book Fair in Rio de Janeiro. First revelation: he's cut back from 34 white suits to a paltry, pauperistic 24. Next revelation: he's ditching fiction for his next book, which will focus on the shabby-chic impulses of executive types. Given Wolfe's keen eye for upper-middle-class pageantry, this sounds like fertile terrain. But oddly enough, he seems less interested in the nostalgie-de-la-boue angle, and more perplexed that America's most eligible bachelors are sending out mixed signals:

After all, what is a rich man who dresses in a style known as post-homeless trying to say? That's what I'd like to find out. That's why there are so many bad marriages. A girl can no longer tell where a young man stands just by looking at him.Time to add another clause to the lovely Defense of Marriage Act, forbidding guys in the top two tax brackets from shopping at Old Navy.

Wednesday, May 11, 2005

John Simon, Gogol's capacious overcoat

According to the Playbill website, John Simon has gotten the boot from New York after serving as the magazine's theater critic for forty (!) years. His propensity for the critical kidney punch has made him plenty of enemies, and yes, he's been capable of out-and-out nastiness. But Simon is never mushy, I'll give him that. And when he climbs onto the moral high ground, he stays there. In his recent review of Glengarry Glen Ross, Simon curled his lip at David Mamet for actually liking his crew of thuggish real-estate operators. Quoting his own review of the original 1984 production, Simon gives Mamet a disgusted slap on the wrist for the way "he revels in their brazen, agile crookedness. This strikes me as reprehensible, immoral." Old-fashioned? Certainly. Prissy? Perhaps. But I have to admire Simon for not budging from his position. At age 79, incidentally, he's determined to keep writing. Where he'll go next isn't yet clear.

In a snippet from a piece in the New York Review of Books (via Rake's Progress), Gary Shteyngart celebrates the Russian satirist Vladimir Voinovich, declaring:

In a snippet from a piece in the New York Review of Books (via Rake's Progress), Gary Shteyngart celebrates the Russian satirist Vladimir Voinovich, declaring:

If all Russian writers (as Dostoevsky said) are supposed to come "from under Gogol's 'Overcoat,'" Voinovich has come directly out of Gogol's 'Nose.'Now, I had a vague memory of seeing that quote attributed to somebody else. And sure enough, when I plugged it into Google, I found it chalked up to Pushkin, Turgenev, and Chekhov as well as Dostoevsky. No hits yet for Boris Badenov, but I'll keep looking.

More Idolatry, more William Logan

It's a good thing the damn show is winding down, because I won't be able to come up with many more punning titles. Anyway, it was a mixed bag tonight, wasn't it? Bo grinned his way through that Travis Tritt piffle the first time around, then made like a rock star during the Gamble-Huff interlude. Carrie notched one of the worst performances ever, leaving "If You Don't Know Me By Now" in an utter shambles, and for once the judges were brutally frank with her. Even the odious Fedorov beat her out on that song, although his first turn was so icky I wanted to pour Listerine in my ears afterward. Sheesh. Vonzell was fine, whatever. Let's just get it over with. Bo and Vonzell will be the last ones standing. Then 30 million Americans will do some wacky calculus--taking into account talent, appearance, regional affinity, and some racial x-factor that I don't even want to imagine--and we'll be left in peace until the next time around.

It may seem that I can't think about American Idol without adverting to William Logan. Not true. I did, however, want to post a favorite passage of mine--a beautiful paragraph that makes the phrase critical prose sound pathetically crabbed and insipid. Hold onto your hats:

It may seem that I can't think about American Idol without adverting to William Logan. Not true. I did, however, want to post a favorite passage of mine--a beautiful paragraph that makes the phrase critical prose sound pathetically crabbed and insipid. Hold onto your hats:

Every poem of value must have a residue. A residue is not a mystery or a withholding. It is the result of a continual ignition in the language, a combustion in the nearness of words--it is what lies beneath the surface value of words. We can wear out a poem as we wear out a favorite jacket or joke. In a minor poem the residue is small and easily exhausted, but in the greatest it suffers a constant renewal. It cannot be exhausted because our lives are not long enough to do so. Indeed, in the greatest poetry the residue may seem to increase as our experience increases--that is, as we become more ruefully sensitive to the fire in its familiar words.Tremendous. I think the greatest prose harbors a similar residue, possibly in a more dilute form. To read the rest you'll have to buy Reputations of the Tongue. Need I say more?

Monday, May 09, 2005

Re: NYTBR

This week's New York Times Book Review featured two irresistible items. First: Butch Trucks, the once-and-future drummer for the Allman Brothers Band, kicks Roy Blount Jr. and (the late) Grover Lewis down the stairs for daring to impugn Duane Allman's character. I relished every word of his righteously indignant letter. I was also delighted to discover that he's a Saul Bellow fan, and that he and Dickey Betts enjoyed debating the finer points of Zen Buddhism when they weren't onstage thrashing their way through "Whipping Post." I'm hoping that next week's issue will include a similarly bristling communication from Jai Johanny Johanson.

Second: there was a very interesting piece by Lee Siegel, in which he takes Freud to task for his destructive impact on imaginative literature. Siegel is a smart guy--also the hardest-working critic in show biz, with regular gigs at The Nation, The New Republic, and Slate--and when I met him recently at a party, we had a nice conversation about a book we've both long admired: Eileen Simpson's Remembering Poets. He's certainly right to argue that Freud's "universal paradigm for the human personality" has turned out to be something of a blunt (and parochial) instrument. Yet another part of his argument seems pretty wobbly--the suggestion that Freud's mechanical notions of human behavior have killed off the "idiosyncratic, original inner and outer lives" of the characters we encounter in postwar fiction.

To buttress this argument, he first cites the nouveau roman. It would be charitable to call that a red herring: the nouveau roman is a gimmick, a cul-de-sac currently occupied by Alain Robbe-Grillet and about 19 readers. Siegel's next bit of evidence--the postmodern novel, with its "self-annulling irony, deliberate cartoonishness, montage-like 'cutting'"--is more persuasive. Still, he manages to bash postwar fiction for its puddle-deep characterization without mentioning a single author. And once you consider some actual examples, the thesis begins to fall apart. Does Siegel really believe that, say, Rabbit Angstrom has no psychological depth as a character? How about Nathan Zuckerman (if anything, we know too much about that guy) or Augie March? I mention Updike, Roth, and Bellow deliberately, because they're not flukey exceptions to the rule: they're mainstream postwar novelists, with large audiences and more decorations and medals than Tommy Franks. But there are plenty of other examples. Are Alice Munro, Charles Baxter, Jane Smiley, David Gates, Penelope Fitzgerald, Tobias Wolff, and V.S. Naipaul (a random sample, really) all so in thrall to Freud that they can't create characters with a 3-D, Victorian amplitude? I just don't see it. Blame the Golden Sigi for his zanier conceptions, sure--but not for the Death of Depth, which I maintain is alive and kicking. (For a different take on the same piece, see Maud Newton's post from the other day.)

Second: there was a very interesting piece by Lee Siegel, in which he takes Freud to task for his destructive impact on imaginative literature. Siegel is a smart guy--also the hardest-working critic in show biz, with regular gigs at The Nation, The New Republic, and Slate--and when I met him recently at a party, we had a nice conversation about a book we've both long admired: Eileen Simpson's Remembering Poets. He's certainly right to argue that Freud's "universal paradigm for the human personality" has turned out to be something of a blunt (and parochial) instrument. Yet another part of his argument seems pretty wobbly--the suggestion that Freud's mechanical notions of human behavior have killed off the "idiosyncratic, original inner and outer lives" of the characters we encounter in postwar fiction.

To buttress this argument, he first cites the nouveau roman. It would be charitable to call that a red herring: the nouveau roman is a gimmick, a cul-de-sac currently occupied by Alain Robbe-Grillet and about 19 readers. Siegel's next bit of evidence--the postmodern novel, with its "self-annulling irony, deliberate cartoonishness, montage-like 'cutting'"--is more persuasive. Still, he manages to bash postwar fiction for its puddle-deep characterization without mentioning a single author. And once you consider some actual examples, the thesis begins to fall apart. Does Siegel really believe that, say, Rabbit Angstrom has no psychological depth as a character? How about Nathan Zuckerman (if anything, we know too much about that guy) or Augie March? I mention Updike, Roth, and Bellow deliberately, because they're not flukey exceptions to the rule: they're mainstream postwar novelists, with large audiences and more decorations and medals than Tommy Franks. But there are plenty of other examples. Are Alice Munro, Charles Baxter, Jane Smiley, David Gates, Penelope Fitzgerald, Tobias Wolff, and V.S. Naipaul (a random sample, really) all so in thrall to Freud that they can't create characters with a 3-D, Victorian amplitude? I just don't see it. Blame the Golden Sigi for his zanier conceptions, sure--but not for the Death of Depth, which I maintain is alive and kicking. (For a different take on the same piece, see Maud Newton's post from the other day.)

Friday, May 06, 2005

Eyes on the (additional) prize

According to this piece in the Guardian, the Man Booker panjandrums have sweetened the pot for their much-vaunted International Prize, by throwing in an additional £15,000 for the winner's translator. Whoopee! When it comes to profits, the translator is traditionally the low man (or woman) on the totem pole, paid on a work-for-hire basis and almost never granted even a microscopic fraction of royalties. How nice, then, to see the Man Booker press release refer to this hapless figure as "the unsung hero of international literature." I like the sound of that.

Wooo wooo is right

In Wired, Ryan Singal writes about the many-splendored uses to which Amazon is putting its bottomless database of digital texts. One of the latest bells and whistles, which I had noticed before but never bothered to explore, is called the SIP, or Statistically Improbable Phrase. According to Bill Carr, the company's head honcho for digital media, this characteristic combo--extracted, I'm sure, by means of some algorithmic trickery--often "gets to the heart of the book." (His example: "adaptive unconscious" as the figure in the carpet for Malcolm Gladwell's Blink. Sounds reasonable.)

Anyway, I wanted to take the SIP technology for a spin, and decided to let it extract the soul, the spirit, the very marrow of Tom Wolfe's I Am Charlotte Simmons. In this case, the ghost in the machine came up with multiple SIPs (not an unusual situation.) And yes, it did get to the heart of the matter. The first ten SIPs from Wolfe's bootylicious doorstopper are: canvas boat bag, caress caress caress, unhh unhh unhh, rutting rutting, sobs sobs sobs sobs, ilial crest, rut rut rut, very hide, wooo wooo, depressed girl. Granted, that last phrase doesn't sound like quintessential Tom Wolfe. But if you had the first nine entries to cope with, you'd be depressed too.

Anyway, I wanted to take the SIP technology for a spin, and decided to let it extract the soul, the spirit, the very marrow of Tom Wolfe's I Am Charlotte Simmons. In this case, the ghost in the machine came up with multiple SIPs (not an unusual situation.) And yes, it did get to the heart of the matter. The first ten SIPs from Wolfe's bootylicious doorstopper are: canvas boat bag, caress caress caress, unhh unhh unhh, rutting rutting, sobs sobs sobs sobs, ilial crest, rut rut rut, very hide, wooo wooo, depressed girl. Granted, that last phrase doesn't sound like quintessential Tom Wolfe. But if you had the first nine entries to cope with, you'd be depressed too.

Thursday, May 05, 2005

On a less ironic note

Last night at around 3:30 AM, two handmade bombs exploded in front of the British consulate, about two blocks from my apartment. Thanks to a half-tablet of Unisom, I heard nothing. Meanwhile, the police and ATF guys have cordoned off the block with yellow tape, and are poking around for clues. Luckily the devices--reportedly cheap, novelty grenade casings filled with gunpowder--injured nobody. They did shatter the glass in the front door and blow out two windows in the Western Publishing HQ across the street. While I stood behind the barrier and took this photo, a grumpy postal worker was trying to empty a mailbox on the corner. A cop shooed him away. I suppose they wanted to make sure there wasn't an explosive party favor in there, too. A nice reporter from a radio station interviewed me in my capacity as an Area Man, but all I could do was make like a cool, crass, imperturbable New Yorker. Which I am. Not.

That creeping irony problem

For some time I've noticed that most of the brief headlines in the Yahoo! In The News box seem to have been plucked directly from the pages of the Onion. A few current samples:

Researchers examine ethics of journalistsCall me crazy, but I can't read these without smirking: they all sound like hidden punchlines. Perhaps the Onion's pitch-perfect parody of headlines has ruined them forever, at least for this Area Man.

Al Gore to get lifetime award for Internet

U.S. can't account for $100M spent in Iraq

Idol update, lost in translation

American Idol got off to a dubious start this evening, with an ensemble performance of "Bridge Over Troubled Waters" that sounded like a very bad college glee club. But it became pretty clear that Bo Bice--that shaggy-maned, coke-snorting son of the South--deserves to win. Meanwhile, after the usual theater-of-cruelty manipulation by the horrible Ryan Seacrest, Scott Savol was chucked off the show. The guy had his problems, including spotty pitch control and that unflattering stubble thing, but there was something very genuine about him. So go figure. An additional gripe: last year, I read that Bob Dylan might do a one-shot judging gig on American Idol, and I'm crushed that he never showed up. (Oh, to hear Anthony Federov sing "Idiot Wind.")

I've been tied up all day with deadline chores--I'm writing a novel with one hand and a new afterword for the paperback edition of Amazonia with the other--which is why I haven't done any blogging until now. But I did want to return to something I touched on in an earlier post: the perils of translation. It's on my mind partly because I've been corresponding with the Japanese translator of Amazonia, who's going far beyond the call of duty--reading the books I mentioned (Nicholson Baker, which makes me feel good) and watching the movies (Dumb and Dumber, which makes me feel guilty.) This degree of diligence is hardly the rule among translators, even very gifted ones. And in that sense, every sentence you translate is a disaster waiting to happen. There are so many ways to foul up: distortions, misreadings, cultural allusions or echoes that go over your head. I hope and pray that I haven't stepped in too many pails of milk myself. And when I get too cocky about my skills, I remind myself of the Italian version of Lolita I once picked up in Rome. In a certain passage, Humbert Humbert mentions Old Faithful--a famous geyser in America, a biblical-sounding obscurity anywhere else--and I was pleased to see a footnote below. But as the translator helpfully explained, Old Faithful was a particular kind of American airplane. Nabokov would have had conniption fits. As a translator, all I can do is shake my head and mutter: There but for the grace of God...

I've been tied up all day with deadline chores--I'm writing a novel with one hand and a new afterword for the paperback edition of Amazonia with the other--which is why I haven't done any blogging until now. But I did want to return to something I touched on in an earlier post: the perils of translation. It's on my mind partly because I've been corresponding with the Japanese translator of Amazonia, who's going far beyond the call of duty--reading the books I mentioned (Nicholson Baker, which makes me feel good) and watching the movies (Dumb and Dumber, which makes me feel guilty.) This degree of diligence is hardly the rule among translators, even very gifted ones. And in that sense, every sentence you translate is a disaster waiting to happen. There are so many ways to foul up: distortions, misreadings, cultural allusions or echoes that go over your head. I hope and pray that I haven't stepped in too many pails of milk myself. And when I get too cocky about my skills, I remind myself of the Italian version of Lolita I once picked up in Rome. In a certain passage, Humbert Humbert mentions Old Faithful--a famous geyser in America, a biblical-sounding obscurity anywhere else--and I was pleased to see a footnote below. But as the translator helpfully explained, Old Faithful was a particular kind of American airplane. Nabokov would have had conniption fits. As a translator, all I can do is shake my head and mutter: There but for the grace of God...

Tuesday, May 03, 2005

Blurbosphere and two from Walden

Did William Safire just awaken from some Rip-Van-Winkle-like slumber? That's the only conclusion I can draw from his latest "On Language" piece, which delivered the astounding news that blurbs on book jackets are not reliable. Holy cow! I believe that the invention of the empty-headed, logrolling blurb came directly after the invention of cuneiform script. To report this as breaking news is something of stretch. (What I would like to read, however, is a survey of the blurbosphere's heaviest lifters. Richard Howard, for example, is rumored to have an entire bookshelf in his apartment devoted to Books I Have Blurbed, and I'm sure there are many other contenders for the throne.)

On other fronts: I read Walden last year, to the dismay of my friends, who were eager for me to get through my American Renaissance phase. (Now I'm better, thank you.) Anyway, there were two passages that I wanted to dredge up. The first seemed highly relevant to my life as a reviewer. Thoreau is talking about a French-Canadian woodcutter he often encountered in the forest around Walden Pond:

On other fronts: I read Walden last year, to the dismay of my friends, who were eager for me to get through my American Renaissance phase. (Now I'm better, thank you.) Anyway, there were two passages that I wanted to dredge up. The first seemed highly relevant to my life as a reviewer. Thoreau is talking about a French-Canadian woodcutter he often encountered in the forest around Walden Pond:

I asked him if he ever wished to write his thoughts. He said that he had read and written letters for those who could not, but he never tried to write thoughts,--no, he could not, he could not tell what to put first, it would kill him, and then there was spelling to attend to at the same time!There you have my professional challenges in a nutshell. As for the other passage, it's a famous zinger from the opening pages of the book, where the author concedes that it's all about him, him, him: "We commonly do not remember that it is, after all, always the first person that is speaking. I should not talk so much about myself if there were any body else whom I knew as well. Unfortunately, I am confined to this theme by the narrowness of my experience." Seldom in the history of literature has anybody tendered so ironic an apology--which is to say, no apology at all. It's funny: the closest Thoreau ever gets to Jerry Seinfeld. It should also be carved on the lintel of every blogger, assuming you can find one. A lintel, I mean.

Monday, May 02, 2005

Mel Gussow

I was sorry to read about the death of Mel Gussow in the New York Times. In the obituary, Jesse McKinley notes that Gussow's interview collections became "staples of college drama curriculums and the libraries of gossip-loving theater fans," and although I don't quite fit into the latter category, Conversations With and About Samuel Beckett is sitting right here on the shelf next to my desk. As the obit also makes clear, Gussow knew how to handicap a horse race: he was an early champion of Albee, Beckett, Pinter, Stoppard, and such (relatively) young Americans as Sam Shepard, David Mamet, John Guare, and Robert Wilson. And let's not overlook this priceless bit:

In a lecture, called "The Role of the Critic," Mr. Gussow told an anecdote about an actor who played the doctor who appears only very briefly in "A Streetcar Named Desire." Mr. Gussow said the actor described the play this way: "It's about this doctor who takes this crazy lady off to an asylum." It taught him much, he said, about what it means to be a player, of any sort, in the theater.

Some final Bellowing

By now the late, great Saul Bellow has been so extensively eulogized that there's not much left to say--certainly not by the likes of me. That won't stop me from smuggling in a couple of footnotes. First: a historical curiosity. When I read an uncorrected proof of Ravelstein back in early 2000, I was startled to come across this description of the protagonist's boyfriend: "Nikki was perfectly straight--straight, by nature, a handsome, smooth-skinned, black-haired, Oriental, graceful, boyish man." Now, Nikki was anything but straight. Could Bellow possibly be unaware of the contemporary sense of that word? You could argue that his lexicon was a little old-fashioned, that he sometimes trafficked in spiffy bits of 1940s slang (at one point the narrator refers to his youth as "my dude days.") But no, that doesn't explain it. Bellow never stopped his uncanny surveillance of the American idiom, and as for being out of touch with pop culture, hell, we're talking about a novel with a cameo appearance by Michael Jackson. Strange, no? When the finished book showed up, that sentence had been changed to: "Nikki was perfectly direct--direct, by nature...." Either some kind soul at Viking said something to the author, or he made the fix himself. I like to think it was the latter--that Bellow's magnificent ear heard the bum note and adjusted it--but in any case, I'm glad he got that (ahem) straight.

Also, a note of puzzlement about Ian McEwan's valedictory op-ed piece in the New York Times of April 7. I admire McEwan, and as for his idolatrous take on Bellow, I second that emotion. But I continue to be perplexed by his favorite specimen of Bellovian prose, which he has not only memorized as a private mantra but used as an epigraph to Saturday. "Well, for instance," it begins, "what it means to be a man. In a city. In a century. In transition. In a mass. Transformed by science. Under organized power. Subject to tremendous controls. In a condition caused by mechanization." And so on and so forth, for another nine sentences, most of them similarly blunt and hortatory. I have to say this is not first-rate Bellow. It sounds like a party plank. It reveals Bellow's sweet tooth for the sort of sociological analysis that almost scuttles Mr. Sammler's Planet. So what the hell, I'll haul out two of my own favorites. The first is from Ravelstein, and certainly serves as an artistic credo:

Also, a note of puzzlement about Ian McEwan's valedictory op-ed piece in the New York Times of April 7. I admire McEwan, and as for his idolatrous take on Bellow, I second that emotion. But I continue to be perplexed by his favorite specimen of Bellovian prose, which he has not only memorized as a private mantra but used as an epigraph to Saturday. "Well, for instance," it begins, "what it means to be a man. In a city. In a century. In transition. In a mass. Transformed by science. Under organized power. Subject to tremendous controls. In a condition caused by mechanization." And so on and so forth, for another nine sentences, most of them similarly blunt and hortatory. I have to say this is not first-rate Bellow. It sounds like a party plank. It reveals Bellow's sweet tooth for the sort of sociological analysis that almost scuttles Mr. Sammler's Planet. So what the hell, I'll haul out two of my own favorites. The first is from Ravelstein, and certainly serves as an artistic credo:

In my trade you have to make allowances, taking all sorts of ambiguities into account--to avoid hard-edged judgments. All this refraining may resemble naïveté. But it isn't quite that. In art you become familiar with due process. You can't simply write people off or send them to hell.The other one, from the second paragraph of Augie March, is more compact, but it still represents a major trade secret, whether you're a Bellovian maximalist or Borgesian minimalist or anything in between: "Everyone knows there is no fineness or accuracy of suppression; if you hold down one thing you hold down the adjoining." Amen.