Wednesday, June 29, 2005

War of the Worlds

To combat my drooping spirits, I went with a friend to War of the Worlds--on opening day, no less. At the multiplex down on Third Avenue, there seemed to be shows about every three minutes, so getting in wasn't a problem. What was a problem was Tom Cruise, no better or worse than ever, but essentially lost without a strong dose of juvenile cockiness. Another problem: Spielberg can't stop repeating himself. A long, freaky, robotic tentacle searches a grimy basement for human prey, much like the mechanical spiders in Minority Report. Then a pack of CGI aliens does a predatory tour of the same basement, much like the CGI dinosaurs racing around the kitchen in Jurassic Park. Needless to say the crew at Industrial Light & Magic knocked themselves out on this one, and the visual effects are often mind-blowing. But for a film full of frenetic crowds and communal mayhem, it feels oddly depopulated. There's Cruise, a divorced father who must repair his half-assed relationship with his daughter and son--and there's everybody else, a million-and-one anonymous extras being vaporized by the tripods or drained of their bodily fluids like walking, or fleeing, Slurpees. Surprise: at the end, it's all about healing the familial rift. Spielberg, a virtuoso confectioner of eye candy, has used the family romance to anchor his sleekest conceits (Catch Me If You Can) and career highlights (E.T., not to mention Schindler's List, where catastrophe also conspired to turn Liam Neeson into a kinder, gentler paterfamilias). At this point, however, the save-the-children motif is beginning to feel reflexive--a soft-centered substitute for the more varied, sometimes nasty emotions that fuel adult behavior the world over. Spielberg will certainly dig deeper. At 59, he's at the top of his game, and even a popcorn spectacular like this one shows off his visual flair and shot-by-shot concision. But maybe next time around, he'll admit that other alien life form to his universe: the sentient, scheming adult.

I'm still here

The taxi to JFK took two hours in the pouring rain. The driver, an older Italian man who kept singing along with the radio (Ti voglio al piu presto sposar and a few other Europop classics) said he had a bad feeling, and he was right: we missed the plane. Crushing. Luckily a Delta telephone rep managed to sneak us onto a flight on Thursday. Until then I'm still here, huddled by the wheezing Amana air conditioner in my office, so what the hell, I'm posting.

About the Mahler: tremendous. Lorin Maazel kept the notoriously centrifugal Sixth on course, with brisk tempos and wonderfully detailed work from the reeds and the brass section. He sandwiched the Andante between the opening Allegro and the Scherzo--the composer kept flipflopping about where to put it during his lifetime--and I was grateful for this bit of stress management, since it gives you a break from the militant Sturm und Drang of the surrounding movements. Perhaps this tampers with Mahler's supposed narrative structure: the tempest-tossed Everyman who finally gets laid low by the two hammer blows of fate. I'm always a little leery of these plot summaries, even when they issue straight from the horse's mouth. Not Anthony Tommasini. His otherwise acute review in the New York Times suggested that Mahler had been channeling Jake La Motta:

About the Mahler: tremendous. Lorin Maazel kept the notoriously centrifugal Sixth on course, with brisk tempos and wonderfully detailed work from the reeds and the brass section. He sandwiched the Andante between the opening Allegro and the Scherzo--the composer kept flipflopping about where to put it during his lifetime--and I was grateful for this bit of stress management, since it gives you a break from the militant Sturm und Drang of the surrounding movements. Perhaps this tampers with Mahler's supposed narrative structure: the tempest-tossed Everyman who finally gets laid low by the two hammer blows of fate. I'm always a little leery of these plot summaries, even when they issue straight from the horse's mouth. Not Anthony Tommasini. His otherwise acute review in the New York Times suggested that Mahler had been channeling Jake La Motta:

As the hero forges ahead with mindless determination, the first hammer blow (made by a percussionist pummeling a great wooden box with a fearsome-looking felt-covered wooden hammer) knocks him loopy. Crazed and wild-eyed, he tries to go on, or so it seems from the frantic outbursts of counterpoint that are scattered in the orchestra. But the second hammer blow levels the hero, and the bucolic music comes back, this time, as performed here, in some unhinged, dissipating state. Imagine a "Star Wars" character being slowly vaporized.About those hammer blows: Alma Mahler alway insisted that they were an eerie anticipation of the misfortunes that were to afflict her husband during the coming year. Get out! Especially because Mahler originally inserted five hammer blows into the score, then cut out three. What he asked for was "a short, loud, but dully resounding blow of non-metallic character (like the stroke of an axe)." To this end he had a gigantic drum constructed in Vienna, which was not a great success. As Henry-Louis de La Grange recounts in his humongo, four-part biography:

At the first of the three readings that took place in Vienna in April, the enormous drum was installed for the first time amid a breathless hush. Mahler asked the percussionist to try it out, but the result was weak and muffled. Despite Mahler's insistence, the musician failed to produce a louder tone and Mahler angrily rushed over and struck the intrument with all his force. The inadequacy of the result compared with the effort required to produce it provoked general hilarity among the musicians.The story of my life. In any case, the hammer blows at the Philharmonic were loud: the people in the first three rows probably had their hair blown back. I couldn't see the drum itself, but the hammer looked like a prop from Land of the Giants, and the percussionist hefted it with obvious relish. One of my companions thought the whole business smacked a little too strongly of Wile E. Coyote--even the jumpcutting textures of the Scherzo struck her as cartoonish--but if pressed, I would be more likely to name Ricochet Rabbit as the symphony's tutelary spirit. On the other hand, I'd probably take the Fourth, or the Third, but not the Sixth, to that proverbial desert island.

Monday, June 27, 2005

HOM on vacation

I'll be out of town--in Turkey, to be precise--from now until July 16, which means that HOM will be on vacation as well. Feel free to rove the archives and leave snarky comments on existing posts until that time. And when I'm back, I'll be blogging at length about Mahler's Sixth (you should have seen the Brobdingnagian croquet mallet they used for the two hammer blows of fate), the new Didion book (excellent, touching, strange), and my favorite newspaper ad of the moment, which begins:

"Live in the sunshine, swim in the sea, drink the wild air," wrote Ralph Waldo Emerson. If you didn't know better, you'd think the great writer was talking about the Hamptons--a destination that's a world apart and offers an ambiance unlike any other.

Friday, June 24, 2005

Idle hands

I just stumbled across this Rolling Stone piece about the ultra-hip appeal of abstinence among twentysomething men. Delayed gratification is fine by me. Wearing a funny plastic bracelet to signify your purity--yes, it's called a masturband--is fine by me. I wasn't even thrown by the fact that all the young, proud virgins in the photo were taking hits off a hookah. But I threw up my non-masturbanded hands when I got to the paragraph about their reading habits, especially that last, surreal sentence, which made me wonder whether these guys shouldn't ease up a little on the hubble-bubble:

Wild at Heart and Eldredge's other best sellers, The Journey of Desire and The Sacred Romance (as well as "field manual" workbooks that can be purchased separately), address sexual "purity" as part of the fabric of Christian manliness. The most important of these books is Every Man's Battle, which, in the past five years, has become a powerful brand name unto itself, with dozens of Every Man spinoff titles: Every Young Man's Battle, Every Woman's Battle, Preparing Your Son for Every Man's Battle and on and on. There's also an Every Young Man's Battle movie filmed on actual battlefields from history and featuring an interview with former NFL player William White and a discussion between Christian-right leader Dr. James Dobson and serial killer Ted Bundy.

Thursday, June 23, 2005

Because it's all about me

All hail Campus Sexpot

Last night I devoured David Carkeet's Campus Sexpot, a narrow-gauge work of autobiography with a donnée to die for: when the author was fifteen, a former teacher at his high school published a potboiler with the identical title. This caused a scandal among the citizenry of sleepy Sonoroa, California, many of whom recognized thinly-disguised versions of themselves among the dramatis personae. It also jump-started Carkeet's education as a sexual being (although he bowed to his mother's wishes by tossing the book in the incinerator) and a writer (ditto). He makes no great claims for the literary merits of this rather quaint specimen of early-Sixties porn: quite the opposite. Yet it still does play a talismanic role for him:

I confess that the good parts work a certain magic on me, but only in a roundabout way, through a historical path where I become a young teenager and understand sex as I understood it at that age. When I read the book now, its verbal avoidance of body parts with which I am actually familiar returns them to a thrilling condition of mystery. I don't have to make an effort to enter this frame of mind. Instead, the words in Campus Sexpot that lead up to a saucy scene fire ancient neurons, and before I know it, I am transported into a state of salacious ignorance.This isn't really a book about sex, of course. In a sense, it's about the slow, steady, mortifying accumulation of worldliness. (Perhaps it should have been called Speak, Puberty.) But Carkeet has also produced a comical hologram of small-town life, where the atmosphere of relative innocence is presided over by the local magistrate, who happens to be Carkeet's father. His verdict on his adult son? "You're a good boy," he tells him on the final page, and the good boy has written a very good book.

Wednesday, June 22, 2005

And while we're at it, let's ban kitchen matches

What a relief to see that in these troubled times, we're going to amend the Constitution to make sure nobody can use the U.S. flag for kindling. I'm not in favor of flag-burning--who is, even among those who insist that such an act is a fiery form of protected speech?--but surely we don't need to clutter up the nation's operating instructions with this pointless codicil. And don't even get me started with the cheap, brass-band patriotism. If you believe in the values enshrined in the flag, then you believe that it takes more than a Zippo to eradicate them. "Ask the men and women who stood on top of the (World) Trade Center," said Rep. Randy (Duke) Cunningham, R-Calif. "Ask them and they will tell you: pass this amendment." To be honest, Duke, I'm sure those men and women are much more concerned with fighting an effective war on terrorism than turning the flag into a fetish object.

My Cold War, New Yorker poetry, pick hits

Last night, after many interruptions, I finally polished off an excellent novel: Tom Piazza's My Cold War. I was already familiar with the author's work as a music critic, having spent hundreds (or was that thousands?) of hours poring over his Guide to Classic Recorded Jazz since it was published by the University Press of Iowa in 1995. But Piazza turns out to be a superbly evocative novelist, with the rare ability to put private life in its public context. The narrator is an academic, with a specialization in Cold War history--his brand of pop-culture careerism put me in mind of the Hitler Studies department in DeLillo's White Noise, although Piazza's slant is less satirical--and his big thing is surfaces: images, ads, iconic bits of footage (hello, Zapruder). Drilling down into the historical machinery strikes him as a distraction. Alas, he applies the same doctrine to family life, which accounts for the many-splendored metaphor of the title. The whole thing is done with great style, wit, and intelligence, and my only regret was that it wasn't twice as long. Special bonus: this is the first book I've encountered since Levon Helm's This Wheel's On Fire to boast a blurb from Bob Dylan.

Just cracked open the latest New Yorker, and so far the poetry department is batting zero for two. Seamus Heaney is a master, but "Chairing Mary" finds him in his slight, sentimental mode. "I think of her warm brow we might have once / Bowed to and kissed before we kissed it cold," he concludes, and not even the late-breaking evocation of last things can yank the stanza back onto its feet. Eliza Griswold's "Buying Rations in Kabul" is hardly a poem at all, more like a repertorial snapshot in rhyme. There are moments when the language grows more taut ("shelf to shining shelf," "thanked us twice for bringing peace") but the ending is clumsy and didactic:

And what about music? What are some of my current, high-rotation favorites? Glad you asked. I've been listening to:

Just cracked open the latest New Yorker, and so far the poetry department is batting zero for two. Seamus Heaney is a master, but "Chairing Mary" finds him in his slight, sentimental mode. "I think of her warm brow we might have once / Bowed to and kissed before we kissed it cold," he concludes, and not even the late-breaking evocation of last things can yank the stanza back onto its feet. Eliza Griswold's "Buying Rations in Kabul" is hardly a poem at all, more like a repertorial snapshot in rhyme. There are moments when the language grows more taut ("shelf to shining shelf," "thanked us twice for bringing peace") but the ending is clumsy and didactic:

Of course they know that any peaceContains? She couldn't do any better than that? Well, I did admire her piece on Waziristan last year. And I haven't read the Robert Hass poem yet, so maybe there's some compensatory joy on page 97. Stay tuned for further developments.

that must be kept by force

contains another name. It's war.

And what about music? What are some of my current, high-rotation favorites? Glad you asked. I've been listening to:

"Go It Alone," from Beck's Guero. I used to think Beck was the white Prince, with an eerie ability to mix and manipulate genres like finger paint. Now I think of him as the American Nick Lowe, with the same troubled relationship to sincerity, even as the real, white-haired Nick Lowe turns into an English Burt Bacharach. None of which truly detracts from the fun.

"Your Love Has Faded," from Johnny Hodges: With Billy Strayhorn and the Orchestra. The incognito orchestra is Duke Ellington's, the arrangements are Billy Strayhorn's, and as for the undulant, erotic alto--nobody's ever topped Johnny Hodges. He's great on the muscular midtempo numbers, like "Don't Get Around Much Anymore" and "Juice A-Plenty," but sublime on the slow stuff, where his expressive glissandi and dynamics will kill you.

"Andante moderato," from Leonard Bernstein's 1988 version of Mahler: Symphony No. 6 with the Vienna Philharmonic. I'm going to see the New York Philharmonic do the mighty Sixth this Friday, so I've been preparing. Can't handle the grinding, minor-key material before noon, but the third movement is Mahler in his melting, pastoral mode, like a warm bath in E-flat major. Lovely. Beautiful, tiered exchanges from the horns at 6:54, with rustic cowbells and clattering agricultural implements off to the left.

Monday, June 20, 2005

Podcasts do blue

According to a rather stuffy-sounding document called "The Podcast Value Chain Report," users are itching for more bootylicious audio. Alex Nesbitt, the author of the report, notes that university lectures and investment research should drive growth in the sector, and that the market for podcasting tools and services will hit $400 million in the near future. But I was shocked, just shocked, to read that erotica remains the most popular category. And as Nesbitt puts it, "The supply is not yet meeting market demands." Studiously ignoring the minefield of double-entendres, he adds: "I speculate that performance-based advertising may develop into a major mechanism." Well, that depends on who's doing the performing.

Althorp, Kabbalah cretins, Lowell, two books, Human Stain on film

Gershom Scholem is doubtless spinning in his grave at the news that the Kabbalah Center in Los Angeles--a celebrity petting zoo stocked with such big-name exhibits as Demi Moore, Ashton Kutcher, and Britney Spears--will be teaming up with Madonna (whoops, I mean Esther) to promote its own brand of bottled water. You just can't make this stuff up. But that's not the worst of it. The founders of the center, Philip and Karen Berg, are concerned that the Jewish mystical tradition is, well, too Jewish, and requires a firm shove into the mainstream. Makes sense, doesn't it? Why bother with the Ten Sefirot or the hidden essence of God when you can peddle red strings to every teenager in America? And those kids will need reading material as well: "Trying to cut the cult from its Jewish roots, [the Bergs] used Craigslist to solicit freelance ghostwriters to help them write 'scholarly' Kabbalah books." The good news: if you buy the book and the bottled water in a single, shrinkwrapped gift pack, they throw in a branded dreidel.

On a more inspiring note, Jonathan Raban has written an eloquent piece about The Letters of Robert Lowell in the latest New York Review of Books. He's very shrewd on the matter of Lowell's reputation, which has sagged pretty seriously since the poet's death in 1977. For example, I had never considered the ways in which Ian Hamilton's biography (which Raban does call "indispensable") subtly takes its subject down a notch by stressing his manic antics: "Where most of the people closest to Lowell saw him as a sane man cruelly afflicted by intermittent bouts of mania, Hamilton was inclined to see his life as one of overwhelming madness punctuated by spells of sanity." In any case, Raban loves the book. Lowell, he asserts, is "one of the finest letter writers in modern literature," and I would absolutely agree. Stick this on the shelf next to the Wilson-Nabokov correspondence, Randall Jarrell's Letters, and Elizabeth Bishop's One Art. (I'm sure there are plenty of others, but I haven't had my second cup of coffee yet.)

"Isobel, who with her leaping breasts / Pursued me through a Summer." Quick quiz: who wrote those lines? Turns out to be Auden, who later said they were the worst he had ever produced, and added that they would have made a perfect caption for a Thurber cartoon. I came across that gem in Humphrey Carpenter's W.H. Auden: A Life, which I've been thumbing through before bed. I've also been reading David Ferry's new translation of The Georgics of Virgil, and have gotten this apocalyptic bit stuck in my head like a Top Forty tune:

At twilight, in the evening, ghosts were seen,Odd. I can't read Latin, so I don't know if the passive, halting, circular sound is true to the original, but it's working for me.

Or strange pale simulacra of human beings;

In a silent grove--many attested to this--

A loud voice was suddenly heard to speak;

And animals, too, were suddenly heard to speak--

Unspeakable!--with the voices of men and women.

Finally, I watched The Human Stain on DVD the other night. It might have worked better as a piece of radio theater. That way, I wouldn't have noticed that Anthony Hopkins wasn't black, or that Gary Sinise wasn't an elderly Jewish writer, or that Nicole Kidman wasn't a homely janitor. In fact Kidman was the most persuasive of the three. On the other hand, she was saddled with the worst scene in the entire film--a cri-de-coeur addressed to a caged crow, which kept tilting its head in disbelief--so I had to dock her another ten points. Yes, I understand that Coleman Silk was passing as a white man. But Hopkins seems so quintessentially Caucasian that I couldn't accept his negritude for a single instant--even Yoda strikes me as a more realistic character. Maybe they should have paid the extra money and gotten Dana Carvey.

Wednesday, June 15, 2005

Kadare: the plot thickens

In my previous post about Ismail Kadare, I alluded to the Albanian novelist's complicated translation history, and urged visitors to read David Bellos's fascinating article on the topic at The Literary Saloon. As Bellos explains, most of the English versions of Kadare's work have derived from French translations, many of them vetted by the author himself. But what then was I to make of my dogeared copy of Chronicle in Stone, which appears to have been translated directly from the Albanian by some anonymous hand? Bellos was kind enough to clear up the mystery via email, and to elucidate what is called (I'm not kidding, and neither is he) the Pipi-Kaka Quarrel.

Just an addendum to your blog piece about Kadare: Chronicle in Stone was translated by Arshi Pipa, an Albanian émigré and professor of Italian literature at Minnesota for many years. There was some disagreement about the translation (with the publisher, with Kadare, I'm not sure) and as a result, in some kind of a huff, Pipa asked his name to be not attached to the book as published. But it is true that it was "translated from the Albanian." Subsequently Pipa rather took against Kadare and there was a public dispute between them (known, I'm told, as the "Pipi-Kaka" quarrel). Pipa died some years ago.

The obvious problem is that Pipa was not a native speaker of English. A less obvious problem is that Chronicle in Stone is translated from the first version, as published in Albania. The text in Kadare's Œuvres complètes is now the definitive version, and a new translation, if one is done, will have to take account of IK's changes.

The Johnson file

Excellent news (reported in the Guardian): Jonathan Coe's biography of B.S. Johnson, Like a Fiery Elephant, has won the Samuel Johnson Award for nonfiction. The ironies are, of course, thick on the ground, since B.S. Johnson's own playful, bristling, increasingly anguished oeuvre won him little acclaim during his short life. (The author committed suicide in 1973, at the age of 40.) And it was Johnson's fealty to fact over fiction--his belief that art was essentially a refined sort of fibbing--that tended to torpedo his own novels. Albert Angelo, one of his best books, collapses during its final pages into an orgy of self-flagellation. And if memory serves me correctly, the author also breaks in at the end of House Mother Normal to admit he was making the whole thing up. Still, they're both tremendous reads, as is the devilish, high-concept Christie Malry's Own Double-Entry. (As usual, The Complete Review features a fine round-up of Johnsonian reviews, quotes, and links.)

With Coe's biography in the spotlight, I have a bonus for HOM visitors: the outtakes from Kerry Fried's Newsday profile of the author, with tons of material that couldn't be shoehorned into a relatively short article. Enjoy!

With Coe's biography in the spotlight, I have a bonus for HOM visitors: the outtakes from Kerry Fried's Newsday profile of the author, with tons of material that couldn't be shoehorned into a relatively short article. Enjoy!

Fried: You dedicated Like a Fiery Elephant to Joyce Yates, whom B. S. Johnson had had a relationship with in the 1950s, and to Julia Trevelyan Oman, a photographer he had worked with. And you clearly became fond of many of the others you interviewed.

Coe: I don't know if that's just because they were being nice to me and seemed generous with their time, which many of them were. But also I did feel--and I don't want to sentimentalize about this--that Johnson himself had been a huge centrifugal force that brought a lot of very disparate people into a kind of community, and when he killed himself that community was shattered and dispersed. One of the roles I found myself playing was that of someone who was bringing those people back together.

Fried: After the biography proper, you intertwine 30 pages of comments from interviews with Johnson's wife, friends, colleagues in "A Life in 44 Voices."

Coe: I began the book with a more conventional, more linear approach but realized that I was approaching the story like the omniscient narrator in a Victorian novel and that wasn't actually what I was: I didn't have omniscience about B.S. Johnson. What's more, it wasn't necessary to do that because many different points of view, including most importantly Johnson's point of view and the point of view of the people who knew him, were available to me and could be presented to the reader more or less unmediated.

Fried: Unlike many biographers of late, you don't explicitly explore the aftermath.

Coe: I think the book had already become so much bigger than I'd imagined or intended and had become so emotionally fraught in many ways--not just in terms of my relationship with the family and how carefully I had to tread round their feelings, but also in terms of the way that B.S. Johnson's state of mind as he kind of came toward to the end was starting to colonize my own state of mind, with a lot of unexpected issues arising out of the writing of the book. All of that made me feel that the death was an absolute cut-off point really, and that there was no point in prolonging the agony by going in any detail into the aftermath or the shock waves that that had sent around his family and friends. I felt I could take all that as given, basically.

Fried: The biography is also enacts your distrust of the silences and compromises of conventional literary biography. One footnote, for instance, reads, "I can't explain this reference." Has that changed at all?

Coe: I've come out of the book with a kind of increased respect for people who have the tact and the confidence to adopt a more omniscient tone of voice and to tread more confidently and assertively rather than the elaborate tiptoeing dance that I perform through a lot of the book.

Fried: Tapdancing, surely. The tension between Johnson's high spirits and his grim vision of society is in your novels, too.

Coe: I don't think that he was more pessimistic about society or human nature than I am necessarily, but that pessimism was much closer to the surface. He could never forget it, or rarely forget it, whereas I'm more like most other people I think, in that I'm able to shut myself off from an awareness most of the time and just get on with life, which is what we all have to do. But we're not dissimilar people in many ways--that's what I discovered when I was writing the book, and I realize now that that's what drew me to him. I thought that what drew me to him was a shared philosophy of experimental writing. But my views on writing and my practice of writing have changed quite a lot in the twenty years or so I've been doing it, and I realize now that what I felt with B.S. Johnson when I first discovered him twenty years ago was a temperamental affinity rather than a theoretical one.

Fried: Is it fair to say that you're preoccupied with the missing? In The House of Sleep Robert disappears and in The Rotters' Club Miriam vanishes.

Coe: I'm just trying to think if there are any missing people in what I'm writing at the moment. Yeah, there are. As you can tell from these books, I am very interested in my relationship to the past and very interested in my relationship to all the people I've known, whether I'm still in touch with them or not. And when people go missing from my life, I do find that intriguing and also frustrating. To go back to the biography, the missing figure is Michael Bannard, who disappeared and weaved in and out of Johnson's story.

Fried: You busted your deadline for Like a Fiery Elephant by some years. Were

you working on it and The Closed Circle concurrently?

Coe: I wrote bits of The Rotters' Club and the biography simultaneously. But

I delivered the first draft of the biography and it kind of shocked Johnson's family, I think. It wasn't the book they were expecting it to be. And there was a necessary period really of about six or nine months where we all just had to stand back and decide what we thought about it. And then what was published was a second draft which in the end wasn't radically different from what I had delivered to start with. That period was a kind of dead period, really. I couldn't really write or concentrate on anything else while I was doing it, so the bulk of The Closed Circle was written more quickly than most of my other novels, in a six-month period between the end of 2003, beginning of 2004.

Fried: Can you say anything more about what you're working on now?

Coe: I have just started something new, which I'm hoping is going to turn into a novel. It's kind of unusual for me, because normally I know whether it's going to turn into a novel or not, and indeed that's how I conceive of it. But I'm being a little more intuitive with this new one and trying to see where the writing leads me. It's good to be writing again, anyway.

Monday, June 13, 2005

Call him Ismail

While the BEA frenzy hit its peak (for a final, palate-cleansing bit of coverage, see my piece in yesterday's L.A. Times Book Review), and while Oprah carpet-bombed America with Faulkner's greatest hits, Ismail Kadare won the first Man Booker International Prize. The Albanian novelist was widely seen as a dark horse, unlikely to prevail against such marquee names as Gabriel Garcia Marquez, Milan Kundera, or Philip Roth. But you know what? If the two books I've read are any indication--we're talking about Chronicle in Stone and The General of the Dead Army--then he deserved it in spades. Kadare is a little hard to describe. He's got a taste for rustic irony--no surprise, since the Albanians have spent the last two millennia hiding out in the mountains from a bumper-to-bumper procession of foreign invaders--but he can also be enchanting, almost wide-eyed, in the freshness of his perceptions.

The prize will earn Kadare £60,000. And since the Man Booker administrators added a secondary purse of £15,000 for the winner's translator, Kadare will be able to share the wealth. Who he'll share it with is something of a vexed question. Most of the English translations of his books have been made from French versions, which the author is said to have vetted quite carefully. (Just to cloud the waters even further: my 1987 New Amsterdam edition of Chronicle in Stone says Translated from the Albanian on the title page, but no translator is listed. Hmmm.) Luckily for us all, The Literary Saloon has posted a superb article on this very subject by one of Kadare's translators (or retranslators), David Bellos. Get over there right away and read it. Then come back.

Last but not least: in 1991 I reviewed The General of the Dead Army for Newsday. Here's the piece in its entirety, for anybody who wants a more detailed look at what is actually Kadare's first novel. (By the way, that OCR software is really something else. And on the Web, this isn't technically self-plagiarizing--it's called repurposing.)

The prize will earn Kadare £60,000. And since the Man Booker administrators added a secondary purse of £15,000 for the winner's translator, Kadare will be able to share the wealth. Who he'll share it with is something of a vexed question. Most of the English translations of his books have been made from French versions, which the author is said to have vetted quite carefully. (Just to cloud the waters even further: my 1987 New Amsterdam edition of Chronicle in Stone says Translated from the Albanian on the title page, but no translator is listed. Hmmm.) Luckily for us all, The Literary Saloon has posted a superb article on this very subject by one of Kadare's translators (or retranslators), David Bellos. Get over there right away and read it. Then come back.

Last but not least: in 1991 I reviewed The General of the Dead Army for Newsday. Here's the piece in its entirety, for anybody who wants a more detailed look at what is actually Kadare's first novel. (By the way, that OCR software is really something else. And on the Web, this isn't technically self-plagiarizing--it's called repurposing.)

Tucked inconspicuously into the flank of the Balkan Peninsula, Albania seldom makes headlines in the West. With its rugged terrain, widespread poverty and a mysterious, umlaut-ridden language, the People's Socialist Republic remains far off the beaten track.

Among European nations, however, it is one of the prime contenders for the dubious, tragic title of Most Often Invaded. The last 2,000 years have seen bloody entrances and exits by Romans, Goths, Bulgars, Normans, Serbs, Venetians and Turks. In our own century, the pace has hardly slowed a whit: the Italians "reclaimed" the country in 1939, followed by the Germans and, sporadically, the Greeks. Only since 1944 have the Albanians had their country to themselves, mostly under the stern Stalinist guidance of Enver Hoxha.

Needless to say, the revolving-door procession of foreign invaders has shaped the Albanian character. Armed resistance is a kind of national religion; a considerable share of Albania's literary tradition celebrates George Kastrioti, better known as Skanderberg, who fought the Turks to a draw for 25 years during the 14OOs.

These days, American readers have the option of viewing this battle-hardened culture through the work of Albania's foremost contemporary writer, Ismail Kadare. Kadare, who was born in 1936 in the mountain town of Gjirokaster, has long has been celebrated in Europe. His 11 novels and numerous volumes of poetry, criticism and short stories have been translated into more than 30 Ianguages. However, little of this work appeared in the United States until 1987, when New Amsterdam Books began an ambitious Kadare-in-every-garage program with Chronicle in Stone. Since then, New Amsterdam has published three more titles: Doruntine (1988), Broken April (1990), and now The General of the Dead Army. All four books disclose a major novelist at work, and one with a storehouse of very persistent, very Albanian themes: invasion, resistance and a corollary tradition of homegrown violence. As one of Kadare's characters says, "In peace, the Albanian becomes sluggish and only half alive, like a snake in winter. It is only when he is fighting that his vitality is at full stretch."

The General of the Dead Army is actually Kadare's first novel, which he wrote in the '60s after having already won a substantial reputation as a poet. It's also his only book to have made a prior appearance in this country. Published in 1973, The General of the Dead Army sank without a trace. Perhaps it will find the audience it deserves in this latest resurrection, though its depressing scenario makes it an unlikely candidate for a commercial chartbuster.

The general in question never is given a proper name. Kadare never even mentions his nationality, although it soon becomes apparent that he's Italian. But he's been sent, sometime during the earIy 1960s, to reclaim the bodies of Italian soldiers who died on Albanian soil during World War II. Wandering "across the country like an ambulatory tumor," with a priest and a platoon of hired gravediggers in tow, he unearths thousands of skeletons.

"I have a whole army of dead men under my command now," he muses. "Only instead of uniforms they are all wearing nylon bags .... At first there had been just a few sections of coffins, then, gradually, companies and battalions were formed." Other voices occasionalIy break in on the narrative--fragments of an Italian soldier's 1943 diary and the italicized thoughts of Albanian bystanders--but the bulk of the novel records the general's disillusionment with his task. Initially, at least, neither the ethics nor the utility of his work bother him much. He recoils instead from the "interminable boredom of the road" and from the mountainous landscape, "the backdrop for some tragedy."

Near the end of his mission, however, the general insists on gate-crashing a peasant wedding in a mountain villa. An angry confrontation occurs. Brought face to face with Albanian resentment, the general's sense of nobility finally begins to wobble. Perhaps there's little point, after all, in "running up hill and down dale sniffing for death like hyenas, trying to find ways of coaxing it or smoking it out of its lair."

The general experiences this illumination while he's dead drunk. And though Kadare doesn't say so, his grave-digging protagonist probably will gloss over the whole thing once his hangover disappears. All of which points to novel's main drawback: the author has tethered the narrative too firmly to general's low-octane imagination. The result, much of the time, is a bland, rather un-Albanian flatness. A useful comparison might be made with Chronicle in Stone, whose young narrator observes the end of a rainstorm over town and notes that "far off, at a distance too great to measure, a rainbow had appeared, like a peace treaty between mountain, river, bridge, torrents, road, wind, and city." Witnessing the identical rain, mountain, river and so on, the general never would notice this multi-colored cease-fire, let alone conflict that preceded it. But then again, he's no Albanian.

Coe conspirator

In yesterday's Newsday, Kerry Fried interviews Jonathan Coe, who has delivered not one but two treats for his fans this year: The Closed Circle (a sequel to The Rotter's Club) and Like a Fiery Elephant (a biography of the cranky and courageous B.S. Johnson). Coe is, not surprisingly, amusing and rather modest. He also makes a neat distinction between his work as a novelist and a biographer. In the first case, he notes, "you're responsible to a kind of larger, more nebulous version of the truth, which is endlessly flexible and very convenient, because it's never specifically defined. Whereas I felt that I had to tread with a certain amount of tact and sensitivity around the facts of B.S. Johnson's life, because his life ended badly and the feelings of all the people involved who survived that act were still pretty raw, and pretty unresolved in some cases as well."

Ship ahoy!

Sorry, I just couldn't stay away from this one, reported last week in the New York Daily News. Apparently Bill O'Reilly had been promoting a special, liberal-hating cruise of the Caribbean, under the winning rubric of "The Battle for American Values." Now, devotees of the No-Spin Zone have every right to pollute the shipping lanes with their blather. And you can't accuse O'Reilly of shortchanging his customers. For a mere $1,099, passengers were slated to enjoy two appearances by the pugilistic host, plus a symposium on "How to Combat the ACLU." Imagine it: the sun, the spray, the icy piña colada--and a strident PowerPoint presentation on the evils of judicial activism. That's certainly my idea of a vacation. Anyway, the whole thing got canceled due to weak ticket sales. Next proposal: a brisk round of paintball with the NARAL staff.

Thursday, June 09, 2005

O, BEA! (Part Four)

The remainder of BEA was, well, anticlimactic. You wouldn't know that from the security guard who noticed my Los Angeles Times badge and excitedly muttered to me, "I've got a story for you." Go ahead, I told her. "Survival of the fittest!" she said. "That's the story of this convention." Perhaps. Yet the floor looked sleepier, less Darwinian, than it had the day before. I wandered down to the basement and caught the tail end of a panel about literary prizes. Then I moved on to another panel on embargoed books, sponsored by the National Book Critics Circle. The participants--from left to right, John Freeman (who looked like he had just run a four-minute mile), David Kipen, Elizabeth Taylor, and Art Winslow--made some amusing and articulate comments about the tug-of-war between publishers (who want to maximize press coverage by sitting on their wares until the last minute) and journalists (who want to report on sensationalistic material the minute they catch wind of it.) One problem: all four panelists were basically in agreement. No kidney punches, no hairpulling, which always enlivens a discussion like this. Everybody complained about "blackout documents," which oblige journalists to delay their reviews until after a certain date. "As a critic," Freeman noted, "you're very sensitive to the feeling that you're just an arm of the publishing industry. That's when I really start to bristle." Kipen suggested a broad-brush solution: "Embargo everything! That way, at least I'll know when I can run the review." A tip of the hat to Art Winslow, for his turn as the soft-spoken devil's advocate. (Addendum: thoughout the entire panel, I could hear a faint, tap-dance-like sound in the row behind me. This was Mark Sarvas of The Elegant Variation, live-blogging the proceedings via a wireless connection. Later I was told he couldn't get a signal and had confined himself to taking notes. So: was it live, or was it Memorex? Does it matter whether he reported on the fly or recollected the whole thing later in tranquility? A tricky question.)

Next I wandered over to the Google booth, with its array of shiny new iMacs, subdued lighting, and the best furniture at the BEA, including a groovy red sofa with cylindrical backrests that was plainly too nice to sit on. Given the recent friction between Google and the publishing community--which now seems to have been resolved--I wondered how smoothly the convention had gone for them. The answer, according to a staffer: very smoothly indeed. Publishers of all sizes had been flocking to the booth to sign up for the Google Print program, clearly figuring that a spot in the company's oceanic database of digitized texts could hardly be bad for business. For a few minutes I hung around and watched publishers enroll in the program: so this was what the radiant future looked like. Then I went to a couple of parties. The first, thrown by HarperCollins, was at Mario Batali's Otto, and I kept imagining I heard the distinctive tattoo of Batali's trademark clogs on the floor. No such luck. It was dark, it was loud, and while I cadged fancy morsels from the passing trays--pizza, shellfish, miniature ice-cream cones I avoided because I assumed they were filled with custard--I saw a few familiar faces drifting by, plus the occasional person I wanted to punch in the back of the head. A pretty good party, in other words. When we stumbled outside it was still bright: blinding, in fact, with a lurid sunset in progress over the Hudson, pale yellow and pink and veined with a fluorocarbon-assisted green. Tortoni is the word that came to mind. We tottered west, toward a party for Toby Young, in a club whose name I honestly can't remember. I was still wearing my narrow, Italianate shoes from the Barney's outlet, and paying the price: a small blister on my left little toe. It slowed my progress. Bliss it was to reach the club, step into the sort of a velvety darkness I associate with a sensory-deprivation tank, and drink a free beer on the banquette. The BEA was over. Long live the BEA, etc.

Next I wandered over to the Google booth, with its array of shiny new iMacs, subdued lighting, and the best furniture at the BEA, including a groovy red sofa with cylindrical backrests that was plainly too nice to sit on. Given the recent friction between Google and the publishing community--which now seems to have been resolved--I wondered how smoothly the convention had gone for them. The answer, according to a staffer: very smoothly indeed. Publishers of all sizes had been flocking to the booth to sign up for the Google Print program, clearly figuring that a spot in the company's oceanic database of digitized texts could hardly be bad for business. For a few minutes I hung around and watched publishers enroll in the program: so this was what the radiant future looked like. Then I went to a couple of parties. The first, thrown by HarperCollins, was at Mario Batali's Otto, and I kept imagining I heard the distinctive tattoo of Batali's trademark clogs on the floor. No such luck. It was dark, it was loud, and while I cadged fancy morsels from the passing trays--pizza, shellfish, miniature ice-cream cones I avoided because I assumed they were filled with custard--I saw a few familiar faces drifting by, plus the occasional person I wanted to punch in the back of the head. A pretty good party, in other words. When we stumbled outside it was still bright: blinding, in fact, with a lurid sunset in progress over the Hudson, pale yellow and pink and veined with a fluorocarbon-assisted green. Tortoni is the word that came to mind. We tottered west, toward a party for Toby Young, in a club whose name I honestly can't remember. I was still wearing my narrow, Italianate shoes from the Barney's outlet, and paying the price: a small blister on my left little toe. It slowed my progress. Bliss it was to reach the club, step into the sort of a velvety darkness I associate with a sensory-deprivation tank, and drink a free beer on the banquette. The BEA was over. Long live the BEA, etc.

Wednesday, June 08, 2005

O, BEA! (Part Three)

That was pretty much it for Friday: I came, I saw, I ate (see photo), I went home. I did spent some time trawling the aisles that afternoon, and overheard some classic snatches of BEA-speak. "I've got some new ideas for how to create transactional television!" "Was that okay, or was it too unpleasant?" "I may have been wrong about wall-to-wall carpeting." But once I retrieved my totes from the chaotic bag check, I went straight back to my apartment. No parties. To be frank, I felt like a candidate for hip replacement. I took off the narrow, punishing shoes I had bought at the Barney's outlet, pored over my precious new galley of Peter Guralnick's Dream Boogie: The Triumph of Sam Cooke (rotten title, but it looks like a tremendous piece of work, with much more detail than Daniel Wolff's You Send Me and the most benign portrait I've ever read of Allen Klein: he sounds like a soul-music Santa Claus, instead of the scam artist depicted in, say, Arthur Kempton's Boogaloo), and fell asleep. When I awoke, it was time for more BEA.

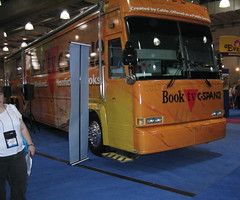

Things were hopping at the Javits Center. Throughout the day, author appearances jammed up the floor: the line for Stacy Schiff, who published the elegant A Great Improvisation in April, included not only history buffs and Ben Franklin freaks but a woman with a sleeping baby on her shoulder. The line for Bill Maher was even longer, and for all I know it included a woman actually giving birth. Rodale staffers had already distributed fans to the masses, each with a discomforting, life-size depiction of Maher's face on one side and the legend I'm a BILL MAHER fan! on the other. Smart marketing. Fanning myself in the crush, I tried and failed to get a decent photo of the wisecracking author, who looks very different with demonic red-eye and no hair. Then I kept moving. I encountered the inevitable guy in a white stormtrooper outfit from Star Wars. I had a chat with Dennis Loy Johnson of Melville House, who was happy to be cohabiting in the "cool aisle" with City Lights, Seven Stories, and various other top-drawer independents. Then I found myself pondering an enormous bus parked on the convention floor--it looked like the Spruce Goose of mass transit--with the Book TV logo proudly emblazoned on the nose. According to Scott Crosby, who patiently fielded my questions while awed C-SPAN fans tried to find some way to clamber on board, this behemoth was about to commence its whistle-stop tour of American letters. (Nonfiction only, of course: Book TV deals with just the facts, ma'm.)

Crosby dwelled on the statistics. "The bus is thirty-five feet long," he said. "Eight feet wide, thirteen feet high." (These are painful numbers for a New Yorker to hear: aside from Donald Trump, almost nobody in Manhattan lives in such a commodious space. Why, there's enough room in there for an alcove study and an EIK.) And what's inside? "The front half contains a fully equipped studio," he told me, "with cameras and flat-screen monitors. In the back half there's an Internet cafe and a control room. So we can actually produce live shows from the bus." The idea is to launch C-SPAN's magical mystery tour in September, at the National Book Festival in Washington, DC, and then keep the vehicle on the road eleven months out of the year. To be honest, the whole set-up had a distinct Austin Powers flavor to it, but there was no mention of a rotating waterbed ringed with clip-on reading lamps from the Levenger catalogue. Look for it in your neighborhood this fall!

Things were hopping at the Javits Center. Throughout the day, author appearances jammed up the floor: the line for Stacy Schiff, who published the elegant A Great Improvisation in April, included not only history buffs and Ben Franklin freaks but a woman with a sleeping baby on her shoulder. The line for Bill Maher was even longer, and for all I know it included a woman actually giving birth. Rodale staffers had already distributed fans to the masses, each with a discomforting, life-size depiction of Maher's face on one side and the legend I'm a BILL MAHER fan! on the other. Smart marketing. Fanning myself in the crush, I tried and failed to get a decent photo of the wisecracking author, who looks very different with demonic red-eye and no hair. Then I kept moving. I encountered the inevitable guy in a white stormtrooper outfit from Star Wars. I had a chat with Dennis Loy Johnson of Melville House, who was happy to be cohabiting in the "cool aisle" with City Lights, Seven Stories, and various other top-drawer independents. Then I found myself pondering an enormous bus parked on the convention floor--it looked like the Spruce Goose of mass transit--with the Book TV logo proudly emblazoned on the nose. According to Scott Crosby, who patiently fielded my questions while awed C-SPAN fans tried to find some way to clamber on board, this behemoth was about to commence its whistle-stop tour of American letters. (Nonfiction only, of course: Book TV deals with just the facts, ma'm.)

Crosby dwelled on the statistics. "The bus is thirty-five feet long," he said. "Eight feet wide, thirteen feet high." (These are painful numbers for a New Yorker to hear: aside from Donald Trump, almost nobody in Manhattan lives in such a commodious space. Why, there's enough room in there for an alcove study and an EIK.) And what's inside? "The front half contains a fully equipped studio," he told me, "with cameras and flat-screen monitors. In the back half there's an Internet cafe and a control room. So we can actually produce live shows from the bus." The idea is to launch C-SPAN's magical mystery tour in September, at the National Book Festival in Washington, DC, and then keep the vehicle on the road eleven months out of the year. To be honest, the whole set-up had a distinct Austin Powers flavor to it, but there was no mention of a rotating waterbed ringed with clip-on reading lamps from the Levenger catalogue. Look for it in your neighborhood this fall!

Tuesday, June 07, 2005

O, BEA! (Part Two)

"How's business?" I asked Mister Dummies, the wide-eyed mascot of the IDG Publishing Group. "Good," replied a muffled voice from deep within the interior. And there did seem to be some general agreement on that score. Stable was the word I heard most often. According to long tall Paul Slovak of Viking, "The market is stable." There were, he admitted, some challenges to be dealt with. "The culture just isn't paying enough attention to books, the way it does to movies or music," he sighed. "Still, in this business, you're obliged to be both pessimistic and optimistic."

I took that to be...optimistic. And certainly that was the note struck by David Poindexter, who runs the San Francisco-based MacAdam/Cage Publishing. We chatted while Poindexter snuck a furtive smoke on some kind of loading dock in back. (If he had been caught, he would have been clapped in irons and flogged on the front steps of Gracie Mansion--but no matter.) It had been a hard couple of years, he conceded, once the post-9/11 recession really hit the book industry. "But I can see it coming back," he said. "The feeling is very upbeat, very positive. We've already given away at least a thousand galleys at our booth. At the last BEA in Los Angeles we did The Time Traveler's Wife, which turned out to be a huge bestseller--and it took us three days to pass out a thousand of those. I think the interest is there again, especially in fiction."

I passed from booth to booth, filling up my tote bags with crap. The BEA is very much an Olde Curiosity Shoppe writ large, and among the faux-medieval scrolls and Rubik's Cube keychains and whale-shaped letter-openers I came across this two-headed goat at the Ripley's booth. (Alas, it was for display purposes only.) More to the point, I began collecting galleys. Two of my favorite prizes--Joan Didion's The Year of Magical Thinking and Gabriel Garcia Marquez's Memories of My Melancholy Whores--were passed off to me discreetly, like contraband. Others were obtainable on the open market: Paul Auster's The Brooklyn Follies, J.M. Coetzee's Slow Man, Elias Canetti's Party in the Blitz: The English Years (which has already created an uproar in the British press for its scabrous critique of Iris Murdoch's erotic performance), Adam Gopnik's The King in the Window, and T.C. Boyle's The Human Fly and Other Stories. And yes, I did succumb to the occasional pitch. "Girls kick ass!" one publicist called out, and suddenly I had my very own copy of Kitty and the Midnight Hour, a werewolf thing.

Whatever. My bags were getting heavier. There was a traffic jam in the aisle, and I darted into a relatively quiet booth, which turned out to be the home of The Book Standard, the new online magazine launched in February by VNU. The editor, Jerome Kramer, filled me in on the details. "The idea was to take all this literary property owned by VNU--a giant, stealthy Dutch conglomerate--and see if we could assemble it into a book-industry portal," he explained. "Publishers Weekly hadn't made any substantial changes in thirty years, and they were very beholden to being a weekly print magazine. We could move much faster. Plus we had the numbers." What he meant was the treasure trove of sales data compiled by Nielsen BookScan, another VNU property. Casual visitors to the site can read a sizeable slice of editorial content. But only subscribers have access to the numbers, which may ultimately siphon off at least part of PW's audience. (Kramer, I should add, was quick to praise his opposite number at the rival magazine: "Sara Nelson was going to be our star columnist until she got that job.")

Now it was time for lunch. I made the mistake of descending into the bowels of the Javits Center, where no sunlight ever penetrates and where the low ceilings and the Nathan's franchise make for a gloomy atmosphere--like a weenie roast in a bomb shelter. It was hard to find a table, harder to find a chair. There were ugly rumors that the convention planners hadn't laid on enough victuals. Still, I bought a sandwich, chewed and swallowed, and then headed back upstairs, where it occured to me for the first time all day that traditional print culture was in some serious trouble. Why? Maybe it was the increased visibility of manga: Viz Media, the producers of My Neighbor Totoro and Full Metal Alchemist, had hung some humongous banners in the lobby, and other manga houses were giving away galleys by truckful. Nothing wrong with manga per se. But I felt a little twinge when I stopped by one of the booths and asked whether the customers were predominantly specialty comics outlets or general bookstores. "We're selling lots of books to classrooms and summer reading programs," I was told. Really? Has Tokyo Boys & Girls finally bumped John Steinbeck off the curriculum? I got a second twinge during my conversation with Steve Emerson and Rich Roberge, two fresh-faced Pepperdine grads who run a company called Rocketbook. Both were wearing bright blue flight suits. The eponymous products are DVD-based study guides, with scads of lively animation and pop quizzes from a guy with heavy stubble and a starched white shirt. "Who's that?" I asked them, as we watched the demo on a big flat-screen unit. "Oh, that's Drew Lavey," they told me. "He's done reporting segments on Ryan Seacrest's show." Really? We're going to learn about King Lear from one of Ryan Seacrest's second bananas? Help! I admit the demo was cleverly done, and might just make the Thane of Cawdor accessible to your average, O.C.-obsessed teenager. I admit to wishing Steve and Rich the very best. But my inner curmudgeon had been summoned from the depths, and if I didn't make peace with him it was going to ruin the rest of the BEA for me.

I took that to be...optimistic. And certainly that was the note struck by David Poindexter, who runs the San Francisco-based MacAdam/Cage Publishing. We chatted while Poindexter snuck a furtive smoke on some kind of loading dock in back. (If he had been caught, he would have been clapped in irons and flogged on the front steps of Gracie Mansion--but no matter.) It had been a hard couple of years, he conceded, once the post-9/11 recession really hit the book industry. "But I can see it coming back," he said. "The feeling is very upbeat, very positive. We've already given away at least a thousand galleys at our booth. At the last BEA in Los Angeles we did The Time Traveler's Wife, which turned out to be a huge bestseller--and it took us three days to pass out a thousand of those. I think the interest is there again, especially in fiction."

I passed from booth to booth, filling up my tote bags with crap. The BEA is very much an Olde Curiosity Shoppe writ large, and among the faux-medieval scrolls and Rubik's Cube keychains and whale-shaped letter-openers I came across this two-headed goat at the Ripley's booth. (Alas, it was for display purposes only.) More to the point, I began collecting galleys. Two of my favorite prizes--Joan Didion's The Year of Magical Thinking and Gabriel Garcia Marquez's Memories of My Melancholy Whores--were passed off to me discreetly, like contraband. Others were obtainable on the open market: Paul Auster's The Brooklyn Follies, J.M. Coetzee's Slow Man, Elias Canetti's Party in the Blitz: The English Years (which has already created an uproar in the British press for its scabrous critique of Iris Murdoch's erotic performance), Adam Gopnik's The King in the Window, and T.C. Boyle's The Human Fly and Other Stories. And yes, I did succumb to the occasional pitch. "Girls kick ass!" one publicist called out, and suddenly I had my very own copy of Kitty and the Midnight Hour, a werewolf thing.

Whatever. My bags were getting heavier. There was a traffic jam in the aisle, and I darted into a relatively quiet booth, which turned out to be the home of The Book Standard, the new online magazine launched in February by VNU. The editor, Jerome Kramer, filled me in on the details. "The idea was to take all this literary property owned by VNU--a giant, stealthy Dutch conglomerate--and see if we could assemble it into a book-industry portal," he explained. "Publishers Weekly hadn't made any substantial changes in thirty years, and they were very beholden to being a weekly print magazine. We could move much faster. Plus we had the numbers." What he meant was the treasure trove of sales data compiled by Nielsen BookScan, another VNU property. Casual visitors to the site can read a sizeable slice of editorial content. But only subscribers have access to the numbers, which may ultimately siphon off at least part of PW's audience. (Kramer, I should add, was quick to praise his opposite number at the rival magazine: "Sara Nelson was going to be our star columnist until she got that job.")

Now it was time for lunch. I made the mistake of descending into the bowels of the Javits Center, where no sunlight ever penetrates and where the low ceilings and the Nathan's franchise make for a gloomy atmosphere--like a weenie roast in a bomb shelter. It was hard to find a table, harder to find a chair. There were ugly rumors that the convention planners hadn't laid on enough victuals. Still, I bought a sandwich, chewed and swallowed, and then headed back upstairs, where it occured to me for the first time all day that traditional print culture was in some serious trouble. Why? Maybe it was the increased visibility of manga: Viz Media, the producers of My Neighbor Totoro and Full Metal Alchemist, had hung some humongous banners in the lobby, and other manga houses were giving away galleys by truckful. Nothing wrong with manga per se. But I felt a little twinge when I stopped by one of the booths and asked whether the customers were predominantly specialty comics outlets or general bookstores. "We're selling lots of books to classrooms and summer reading programs," I was told. Really? Has Tokyo Boys & Girls finally bumped John Steinbeck off the curriculum? I got a second twinge during my conversation with Steve Emerson and Rich Roberge, two fresh-faced Pepperdine grads who run a company called Rocketbook. Both were wearing bright blue flight suits. The eponymous products are DVD-based study guides, with scads of lively animation and pop quizzes from a guy with heavy stubble and a starched white shirt. "Who's that?" I asked them, as we watched the demo on a big flat-screen unit. "Oh, that's Drew Lavey," they told me. "He's done reporting segments on Ryan Seacrest's show." Really? We're going to learn about King Lear from one of Ryan Seacrest's second bananas? Help! I admit the demo was cleverly done, and might just make the Thane of Cawdor accessible to your average, O.C.-obsessed teenager. I admit to wishing Steve and Rich the very best. But my inner curmudgeon had been summoned from the depths, and if I didn't make peace with him it was going to ruin the rest of the BEA for me.

Monday, June 06, 2005

O, BEA! (Part One)

Outside the Javits Center, it was drizzling. Inside, a bagpiper was doing his theater-of-cruelty thing while we waited on the registration line. There were ads for Poland Spring water on the giant monitor, and images of the late Mister Rogers, and I was at Book Expo America once again. My press tag identified me as a creature of the Los Angeles Times Book Review, and more than one conventioneer innocently asked me if I was the new editor. I was tempted to, you know, neither confirm nor deny--but it would have been wrong.

James Fenton once described a visit to Prek Chak, a tiny Cambodian village notorious for its gambling mania. "Absolutely everybody was gambling," he wrote. "It was like, I suddenly thought, coming into some allegorical town, say in the Pilgrim's Progress." For some reason this year's Book Expo gave me a similar impression. Small Press Distributors was raffling off a Dean & Deluca gift basket. Stonebridge was raffling off a sex machine (sorry, I didn't get the details). Random House was raffling off two tickets to a lecture by the Dalai Lama. And the Running Press, in a serious upmarket move, was raffling off a Mini Cooper convertible. Perhaps there's some subliminal message here: after all, any book without the words Harry and Potter on the spine is something of a gamble itself. In any case, I succumbed to gaming fever by Saturday afternoon and did sit down for a hand of poker with Cat Hulbert, anointed "the world's greatest female gambler" by the Game Show Network. She's got quite a set of hands. "Position, position, position," she kept saying. "Here comes the flop." I quickly folded and slunk away from the table. "At least you're leaving with your pants on," she called out by way of goodbye.

The first author I encountered on the floor was Robert Pinsky, who was on hand to promote his boffo Life of King David. Clearly we're not in Sunday school anymore (the third chapter begins with the promising line: "They were polygamists, these monotheists.") Pinsky has drawn on both biblical literature and the Psalms to reinvent this heroic figure, and in a few brief, scarily articulate comments, his explained his attraction to the subject. "David was a great man, a great killer, and a great poet," he told me. "When he got to Heaven, God called up the legal angels and basically got David a seventy-year extension. It's the story, not the biblical element, that drew me to him."

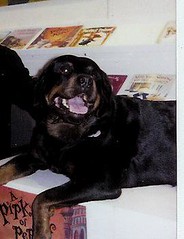

Celebrities are, of course, a dime a dozen on the BEA floor. In short order I spied John Waters--the pencil mustache and S-shaped posture are a dead giveaway--and R.L. Stine and a peevish Nikki Giovanni, bursting out the scrum near the Norton booth and asking her companion, "Where's Penguin? Do you know where Penguin is?" I saw Peter Lawford's son. I saw Tab Hunter, barricaded behind a display of posters and galleys and Tab Hunter refrigerator magnets, signing memorabilia. (The former teen star looked remarkably well preserved, with big hands and a bulletproof tan. When I asked him how it felt to be promoting his autobiography, he said: "Better to hear the story from the horse's mouth than some horse's ass." Touché.) Still, the celeb with the most gravitas was probably Carl, the peace-loving Rottweiler who's made numerous appearances in Alexandra Day's classic series. I joined the long line at the FSG booth, and was treated to various bits of cynical speculation while I waited. "That's actually the fourth Carl," one killjoy said. "I think he's actually a she," piped up another. I ignored them all, wanting to maintain my childish innocence just a little bit longer. While Alexandra Day signed my copy of Carl's Sleepy Afternoon, I asked whether this would be the last Carl book. "It's the last one in the contract," she replied, adding some loop-the-loops to her signature. Then it was time for my audience with the great hound himself, or herself, who smelled my hand for an instant but otherwise peered off into the distance, trying to stay in character.

James Fenton once described a visit to Prek Chak, a tiny Cambodian village notorious for its gambling mania. "Absolutely everybody was gambling," he wrote. "It was like, I suddenly thought, coming into some allegorical town, say in the Pilgrim's Progress." For some reason this year's Book Expo gave me a similar impression. Small Press Distributors was raffling off a Dean & Deluca gift basket. Stonebridge was raffling off a sex machine (sorry, I didn't get the details). Random House was raffling off two tickets to a lecture by the Dalai Lama. And the Running Press, in a serious upmarket move, was raffling off a Mini Cooper convertible. Perhaps there's some subliminal message here: after all, any book without the words Harry and Potter on the spine is something of a gamble itself. In any case, I succumbed to gaming fever by Saturday afternoon and did sit down for a hand of poker with Cat Hulbert, anointed "the world's greatest female gambler" by the Game Show Network. She's got quite a set of hands. "Position, position, position," she kept saying. "Here comes the flop." I quickly folded and slunk away from the table. "At least you're leaving with your pants on," she called out by way of goodbye.

The first author I encountered on the floor was Robert Pinsky, who was on hand to promote his boffo Life of King David. Clearly we're not in Sunday school anymore (the third chapter begins with the promising line: "They were polygamists, these monotheists.") Pinsky has drawn on both biblical literature and the Psalms to reinvent this heroic figure, and in a few brief, scarily articulate comments, his explained his attraction to the subject. "David was a great man, a great killer, and a great poet," he told me. "When he got to Heaven, God called up the legal angels and basically got David a seventy-year extension. It's the story, not the biblical element, that drew me to him."

Celebrities are, of course, a dime a dozen on the BEA floor. In short order I spied John Waters--the pencil mustache and S-shaped posture are a dead giveaway--and R.L. Stine and a peevish Nikki Giovanni, bursting out the scrum near the Norton booth and asking her companion, "Where's Penguin? Do you know where Penguin is?" I saw Peter Lawford's son. I saw Tab Hunter, barricaded behind a display of posters and galleys and Tab Hunter refrigerator magnets, signing memorabilia. (The former teen star looked remarkably well preserved, with big hands and a bulletproof tan. When I asked him how it felt to be promoting his autobiography, he said: "Better to hear the story from the horse's mouth than some horse's ass." Touché.) Still, the celeb with the most gravitas was probably Carl, the peace-loving Rottweiler who's made numerous appearances in Alexandra Day's classic series. I joined the long line at the FSG booth, and was treated to various bits of cynical speculation while I waited. "That's actually the fourth Carl," one killjoy said. "I think he's actually a she," piped up another. I ignored them all, wanting to maintain my childish innocence just a little bit longer. While Alexandra Day signed my copy of Carl's Sleepy Afternoon, I asked whether this would be the last Carl book. "It's the last one in the contract," she replied, adding some loop-the-loops to her signature. Then it was time for my audience with the great hound himself, or herself, who smelled my hand for an instant but otherwise peered off into the distance, trying to stay in character.

Wednesday, June 01, 2005

Information wants to be free

In the freebie newspaper I always read on the subway--where else would I learn the key details about that Christian Slater buttock-groping incident?--I just read that the New York Times is going to start publishing...a freebie newspaper. (As it turns out, the info comes from this piece by Matthew Flamm in Crain's New York Business.) MarketPlace, described as a "full-color, tabloid-sized classified advertising guide spiced up with articles reprinted from the daily paper," will hit the streets on June 9, with an initial print run of 150,000 copies per day. A word of advice to the Gray Lady: if you want to knock A.M. New York out of the box, you'll have to cover the important stuff, like the impending branded-beverage showdown between Nelly's Pimp Juice, Russell Simmons's Def Con 3, Lil' Jon's Crunk Juice, and Master P's King of Energy. Another piece about ergonomically engineered golf clubs just won't do the trick.