Monday, August 01, 2005

Roth, Last Days

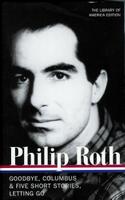

The other day I got the first two volumes of the Philip Roth series from the Library of America: he's the third living author to make the cut, after Eudora Welty and Saul Bellow. Longtime subscribers to LOA will recall the rather chaste jacket art of the initial entries (when your fat, Smyth-sewn edition of Debate on the Constitution: Volume Two showed up in the mailbox, there was no effort to seduce you with eye-catching graphics.) These babies, however, both feature snazzy photos of Roth, first as a Weequahic Lothario with a cushiony underlip, then as the prematurely middle-aged guy who assembled such literary bottle rockets as Portnoy's Complaint and The Breast. Fascinating. Even more fascinating, however, is the precocious brilliance of Goodbye, Columbus, which the author published at the age of 26. Writers twice his age still find it hard to come up with such vivid, funny, anthropologically exact sentences:

The other day I got the first two volumes of the Philip Roth series from the Library of America: he's the third living author to make the cut, after Eudora Welty and Saul Bellow. Longtime subscribers to LOA will recall the rather chaste jacket art of the initial entries (when your fat, Smyth-sewn edition of Debate on the Constitution: Volume Two showed up in the mailbox, there was no effort to seduce you with eye-catching graphics.) These babies, however, both feature snazzy photos of Roth, first as a Weequahic Lothario with a cushiony underlip, then as the prematurely middle-aged guy who assembled such literary bottle rockets as Portnoy's Complaint and The Breast. Fascinating. Even more fascinating, however, is the precocious brilliance of Goodbye, Columbus, which the author published at the age of 26. Writers twice his age still find it hard to come up with such vivid, funny, anthropologically exact sentences:It was, in fact, as though the hundred and eighty feet that the suburbs rose in altitude above Newark brought one closer to heaven, for the sun itself became bigger, lower, and rounder, and soon I was driving past long lawns which seemed to be twirling water on themselves, and past houses where no one sat on the stoops, where the lights were on but no windows open, for those inside, refusing to share the very texture of life with those of us on the outside, regulated with a dial the amounts of moisture that were allowed access to their skin.And to think that he got better as he went along. (Vital trivia: the narrator's name is, of course, Neil Klugman, and the fact that Jack Klugman played Mr. Patimkin in the movie has now introduced just a touch of cognitive dissonance into my reading experience.)

And then there is Last Days, Gus Van Sant's imaginative spin on what we might call Kurt Cobain's exit strategy. The first thirty minutes have a loopy integrity of their own: with nary a line of dialogue, we follow Blake, the Cobain-like protagonist, as he wanders through the woods, pours himself a bowl of Cocoa Puffs, and collapses on the bedroom floor. From the outside, his hilltop mansion resembles a robber baron's wet dream. Inside, with its scabby paint and peeling wallpaper, the place looks like William Burroughs was the decorator. The metaphor--rosy exterior, crumbling interior--fits Blake to perfection. To his credit, however, Van Sant doesn't lean too hard on it. Nor does he inject much pathos or suspense into the situation. It's clear that this guy is going to die, and the only question is: when? What Blake doesn't say--and believe me, he doesn't say much--is conveyed by the long, melancholy, middle-distance shots, the brilliant sound design, and the director's chronological loop-the-loops. Caveat: I was ready for Blake to keel over about a half-hour before the film ended.