Wednesday, November 30, 2005

LATX2, poets online, Rummy's dirty word, Duke departs

There is also an unquantifiable but important cultural factor: There is a strong feeling within the newsroom at the Los Angeles Times that its Chicago masters regard Los Angeles as an alien planet whose denizens are made of different DNA. Chicago's faint and unenthusiastic recognition of the 13 Pulitzers the paper was awarded during the five years that John Carroll was its editor is a wound that refuses to heal. It's almost as if Mars had conquered Jupiter but somehow, much to the Martians' bafflement, Jupiter still exercises a larger gravitational pull and looms still brighter in the heavens above. More than one high official of the paper has remarked on the odd but palpable admixture of resentment and envy the paper's Midwestern owners evince when they are in the presence of their West Coast underlings.On a more cheerful note, Andrew Motion--British poet laureate and the author of Philip Larkin: A Writer's Life--has launched a new site called The Poetry Archive, featuring recordings of poets reading their own verse. In a statement quoted in the New York Times, Motion seemed rather defensive about having the poets do their own dirty work, as opposed to, say, Meryl Streep:

Actors may (or may not) read poems well, but poets have unique rights to their work, and unique insights and interests to offer as we hear their idiom, pacing, tone and emphases. They all, in their different ways, validate the intention of the archive to preserve the mystery of poetry while tearing away some of the prejudices which can make it appear unduly 'difficult' or separate from familiar life.Hear, hear. The site looks great--a gem, really--but despite a good deal of angry fiddling with RealPlayer, I couldn't manage to hear Yeats recite "The Lake Isle of Innisfree." Woe is me. I'll try again tomorrow.

Finally, two political notes of interest. During a meeting with reporters yesterday, semantician-at-large Donald Rumsfeld banned the use of insurgents from his private lexicon. Henceforth Rummy will call them Enemies Of The Legitimate Iraqi Government--a phrase that will instantly double the length of every Defense Department briefing. Please, please, read the entire article here. It's almost indistinguishable from something you might see in the Onion.

Meanwhile, Representative Randy "Duke" Cunningham--whose efforts on behalf of the anti-flag-burning amendment to the Constitution have previously made me apoplectic--will be departing the House in a squalid burst of glory:

Meanwhile, Representative Randy "Duke" Cunningham--whose efforts on behalf of the anti-flag-burning amendment to the Constitution have previously made me apoplectic--will be departing the House in a squalid burst of glory:U.S. Rep. Randy "Duke" Cunningham, a California Republican, fought back tears as he resigned on Monday after pleading guilty to taking $2.4 million in bribes in exchange for help in securing Defense Department contracts. Cunningham, 63, an eight-term congressman and decorated Vietnam War pilot, admitted taking cash, antiques, a yacht, vacation expenses and money for his daughter's graduation party from several defense contractors between 2000 and 2005.It really does call to mind Samuel Johnson's famous definition of patriotism: the last refuge of a scoundrel. Bye-bye, Duke. Write if you get work.

Monday, November 28, 2005

More on Google, Moore on the Edsel

Can they prevail? John Heilemann, in the current New York magazine, seems skeptical. He chats with AAP honcho Pat Schroeder--whose speedy alternation of chuckling defiance and funereal solemnity suggests a multiple personality disorder in the making--and Simon & Schuster CEO Jack Romanos, who has zero tolerance for the search-engine utopians. Romanos complains:

There’s sort of this innocent arrogance about them. One minute they’re pretending to be all idealistic, talking about how they’re only in this to expand the world’s knowledge, and the next they’re telling you that you’re going to do it their way or no way at all. We bent over backwards in negotiations, but they showed no interest in what we had to offer. They had a holier-than-thou attitude that hasn’t done them any favors.Romanos's frustration is easy to understand. What's more confusing is how the whole mess is going to play out. Heilemann gets Lawrence Lessig on the horn, and even the panjandrum of the Creative Commons throws up his hands in despair at the tangle of fair-use law: "There are parts of it that I don’t understand, and I've been studying it for years."

Well, I've been studying it for weeks, and I don't understand it either. But according to the stuff I've been reading on the Web, a crucial precedent for Google in its legal headbutting with AAP and the Authors Guild may be Kelly v. Arriba Soft, a decision handed down by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals in July 2003. In the case, a photographer named Les Kelly sued Arriba Soft, a search engine, for serving up thumbnail images of his landscape photos. Kelly and his lawyer argued that Arriba Soft's use of the photos was not transformative: the search engine had neither added to nor subtracted from the original, full-size images, and was therefore simply stealing them for its own commercial gain. The court threw that one back in their faces. What matters, according to the decision (you can read the whole thing here, in PDF format) is the function of the recycled material. Kelly's original images are panoramas of the American West, designed to aerate and expand the viewer's consciousness. Nobody's going to get a hit of the sublime from an image the size of a postage stamp, argues the court:

[4] Although Arriba made exact replications of Kelly’s images, the thumbnails were much smaller, lower-resolution images that served an entirely different function than Kelly’s original images. Kelly’s images are artistic works intended to inform and to engage the viewer in an aesthetic experience. His images are used to portray scenes from the American West in an aesthetic manner. Arriba’s use of Kelly’s images in the thumbnails is unrelated to any aesthetic purpose. Arriba’s search engine functions as a tool to help index and improve access to images on the internet and their related web sites. In fact, users are unlikely to enlarge the thumbnails and use them for artistic purposes because the thumbnails are of much lower-resolution than the originals; any enlargement results in a significant loss of clarity of the image, making them inappropriate as display material.From Google's point of view, you can see where this is going. Namely: serving up little snippets of copyrighted works is not an attempt to duplicate the aesthetic experience of reading the actual book.

Kelly asserts that because Arriba reproduced his exact images and added nothing to them, Arriba’s use cannot be transformative. Courts have been reluctant to find fair use when an original work is merely retransmitted in a different medium. Those cases are inapposite, however, because the resulting use of the copyrighted work in those cases was the same as the original use. For instance, reproducing music CDs in computer MP3 format does not change the fact that both formats are used for entertainment purposes. Likewise, reproducing news footage into a different format does not change the ultimate purpose of informing the public about current affairs.

Finally, Andrew Wylie puts in his two cents. The Jackal's piece in The Times of London is a little opaque (favorite simile: he compares the "scattering of worthwhile books" in a chain store to "teenage orphans in a roomful of sluts.") Still, he clearly wants to protect the rights of his client base, which makes sense: "We're at a decisive point in the development of our industry, and it's my view that leading agents and publishers should convene to develop working models for these rights. In most areas, for the time being, perspectives should be aligned."

On another note entirely: multitasking Marianne Moore helps out the automotive industry. This sterling anecdote comes from William Logan's new collection The Undiscovered Country: Poetry in the Age of Tin (more on that later).

The Ford Motor Company asked her to help name a new car, then apologetically, and with great delicacy, rejected her bizarre suggestions: the Intelligent Whale, the Arcenciel, the Mongoose Civique, the Pastelogram, the Turcotingo, and, surely the weirdest and most delightful, the Utopian Turtletop. The company decided to call this famous disaster of design the Edsel.

Wednesday, November 23, 2005

What about Bob?

In the current New York Observer, Chris Lehmann sticks it to Bob Woodward, whose vaunted access to the corridors of power has finally gotten him into a mess. It's bad enough that Woodward conveniently forgot about his Plame-related conversation with a "senior White House official" until after Patrick Fitzgerald snapped the (figurative) cuffs on Scooter Libby. But as Lehmann sees it, the trouble goes deeper than a fuzzy memory. Woodward's symbiotic relationship with his sources has effectively defanged his reporting, and suffused it with a bland, backslapping atmosphere of cameraderie:

In the current New York Observer, Chris Lehmann sticks it to Bob Woodward, whose vaunted access to the corridors of power has finally gotten him into a mess. It's bad enough that Woodward conveniently forgot about his Plame-related conversation with a "senior White House official" until after Patrick Fitzgerald snapped the (figurative) cuffs on Scooter Libby. But as Lehmann sees it, the trouble goes deeper than a fuzzy memory. Woodward's symbiotic relationship with his sources has effectively defanged his reporting, and suffused it with a bland, backslapping atmosphere of cameraderie:Yet the surprise Woodward chapter in the Plame affair has less to do with the ethics of reporting than with the theology of access, a spiritual discipline in which Mr. Woodward is undeniably the high priest. His weirdly overlapping books on Bush-era warmaking come overstuffed with self-regarding quotes from all levels of White House officialdom, all the way up to the President himself. All of Mr. Woodward’s sources--on the record and off, and every shade in between--rush to avail themselves of Mr. Woodward’s sourcely solicitude, because they know that he will faithfully transcribe the details of their self-regard most precisely, each in their own grandiose chosen formulations.I've had my doubts about Woodward's books for a long time. In 1996 I reviewed The Choice for an excellent but short-lived monthly called The Midwesterner. Here are a couple of my caveats:

This is the social compact on display in each entry of Mr. Woodward’s sprawling corpus of inside-Washington books, and it also explains the oddly inert quality that nearly all of them share. For all their topicality, Mr. Woodward’s chronicles of the major political events and players in our age never truly manage to get behind the scene, in the way most reporters understand that phrase. They are, rather, extended studies of mise-en-scène, with each source serving as his own director and the author hovering above events as producer and dealmaker, in a studied posture of noncommittal bemusement that he is pleased to consider both fair and balanced.

The fact is that Woodward has a second-rate novelist's grasp of character. He's dependent on a handful of formulaic devices, such as the old Bundle of Contradictions. Colin Powell, for example, "was a passionate person who could also be a cool analyst. He was sometimes profane but also the one to say, 'Yes, sir, Mr. President....' He could also be open, almost confessional, but also he was very public relations-conscious and could close down. There was a core of compassion, even a genuine tenderness to him, but he could be hard."Of course, Clinton is (and was) a compulsive waffler. I'm not suggesting that Woodward's portrait here was incorrect. But we get no nuance, no sense of genuine discovery--just reheated leftovers. Nor, in this case, did Woodward reveal much about the gladiatorial contest between Bob and Bill. What we really learn about are the second-tier handlers and ideological cosmeticians, who have turned so much of our political culture into a farce:

Plumbing the mystery of a human personality--especially one as devious and denial-prone as your average politician's--requires more delicacy than Woodward seems able to muster. As a result, his dual portrait [of Robert Dole and Bill Clinton] leans heavily on cliche. Dole comes off as a paragon of homespun dignity, whose fractured syntax is the very token of his sincerity, while Clinton is a compulsive waffler, frantically trimming his sails to the prevailing political winds.

Woodward has padded The Choice with endless staff meetings, in which flacks, pollsters, and speechwriters debate the best way to slip their candidates past the public's defenses. It might be argued that such sessions are the meat and potatoes of a political campaign, and as such deserve to be at center stage. It's also true that these aspring kingmakers are the source of much unintentional comedy. (My heart certainly went out to Powell booster Stephen Ambrose, who "crafted a first draft of an announcement speech for Powell but complained...that he didn't know Powell's views, cadence, or language, making it difficult to polish such a speech." Somebody, please, get this man a job.)

On the other hand, few readers will feel their pulses quicken as they read about the catfighting among Pete Wilson's inner circle. And the relentness focus on flackery raises a disturbing question. Did these spin doctors win their leading roles in The Choice primarily because they were so available to Woodward? Or has our national politics truly devolved into a Battle of the Handlers, who merely position and reposition their passive patrons to offend the least number of voters? Let's hope--no, let's pray--that the former answer is the correct one.

Tuesday, November 22, 2005

Lowell on sentimentality, Donna Seaman

I think a lot of the best poetry is. Laforgue--it's hard to think of a more delightful poet, and his prose is wonderful, too. Well, it's on the verge of being sentimental, and if he hadn't dared to be sentimental he wouldn't have been a poet. I mean, his inspiration was that. There's some way of distinguishing between false sentimentality, which is blowing up a subject and giving emotions that you don't feel, and using whimsical, minute, tender, small emotions that most people don't feel but which Laforgue and Snodgrass do. So that I'd say he had pathos and fragility--but then that's a large subject, too. He has fragility along the edges and a main artery of power going through the center.In the Chicago Tribune, Mara Tapp interviews Donna Seaman, whose own interviews (this is getting very circular) have recently been collected in Writers on the Air. For Seaman, the minutiae of literature are obsessively compelling, the way baseball cards are for 11-year-old fanatics--she'll trade you two Margaret Atwoods for a rare Aleksandar Hemon:

When I speak to other people who are readers, I feel that we have these maps in our head, like constellations, and they sort of light up, so this was my attempt to turn it into something concrete and to capture those conversations I've had with big readers, many of whom were in the book. You know little boys who are baseball fanatics and keep statistics? It was kind of like that, trying to create a world that you love.

Monday, November 21, 2005

Jonathan Raban, some reviews, Donald Fagen on Ray Charles, the last laugh

In The Seattle Weekly, Tim Appelo (with whom I shared an office at Amazon) sings the praises of peripatetic homebody Jonathan Raban. The occasion, more or less, is the publication of Raban's collection of political journalism, My Holy War: Dispatches From the Home Front. But the article--half critical inquiry and half Q-and-A--examines the ongoing paradoxes of Raban's career, and brushes aside the misnomers (travel writer, regional writer, man without a country) that have stuck to him for nearly three decades. It's an excellent piece, and I'm not saying that just because Tim quoted me. I promise!

In The Seattle Weekly, Tim Appelo (with whom I shared an office at Amazon) sings the praises of peripatetic homebody Jonathan Raban. The occasion, more or less, is the publication of Raban's collection of political journalism, My Holy War: Dispatches From the Home Front. But the article--half critical inquiry and half Q-and-A--examines the ongoing paradoxes of Raban's career, and brushes aside the misnomers (travel writer, regional writer, man without a country) that have stuck to him for nearly three decades. It's an excellent piece, and I'm not saying that just because Tim quoted me. I promise!Meanwhile, Kerry Fried (with whom I shared an office at Amazon) raves about Edith Milton's The Tiger in the Attic in Newsday, noting that the author's "pixillated portraits are among her memoir's great pleasures and recall Penelope Fitzgerald's instant comical epiphanies." In the same newspaper, Nina Mehta (with whom I currently share an entire apartment) doles out more measured praise for Joyce Carol Oates's Missing Mom. She's almost driven mad by one particular linquistic tic: "In Oates's lexicon, the word 'almost' regularly appears in a strange position in sentences. Whether this is sloppiness or a fetishistic use of a word suggesting the incipient nature of an event or thought is anyone's guess, but it is an irritating quirk." And finally, David Kirby (with whom I share no rooms but a great many enthusiasms) wrote this whip-smart appreciation of Peter Guralnick's Dream Boogie in the Providence Phoenix.

Cruising the Web not long ago, I came across Donald Fagen's site, which has an agreeably amateurish feel to it--unlike, say, the entire Steely Dan catalogue. One item I particularly liked was Fagen's tribute to Ray Charles, with its shrewd grasp of the singer's fallow decade:

But I also relished Fagen's winning, whining introduction, where he explains how the piece ended up on his site:Ray's attempts to jump on the funkwagon were half-hearted. The new black sound was colder and right up in your face, based, in fact, on a smaller division of the beat. Brown, Barry White and Rick James seemed less interested in pleasing a woman than in collecting body parts. In contrast, Ray's sage interpretation of "America the Beautiful" (1972) was at once a taunt, a healing gesture, and a blind man's dream of the Promised Land. Perhaps a eulogy as well.

When Ray died, I wrote the item below. Because I know a guy who works for another guy, etc., I had reason to believe this article might appear in a major top-hatted, monocle-wearing magazine. But by the time the editor got the piece Ray had been dead for A WHOLE WEEK so it was no dice. So then the guy I know sent it to a major, tragically hip-to-be-square, Doonesbury-carrying web magazine. They said O.K. but, because they'd already run a piece on Ray, they wanted me to rewrite it to fit in with some format where when-you-click-a-song-title-you-hear-music, blah, blah. Too much work. So I sent it to a woman I know who, once a month or so, manages to put out a very, very thin, in fact, exquisitely thin political journal on special, painfully thin paper. Again, I was too late, they had just gone to press with a Ray piece.And on a related (if somewhat squalid) note, authors can now fight fire with fire when those boilerplate rejection letters start piling up. As Terry McConnell reports in The Edmonton Journal:

I thought, well, alright then. Since I have this new squeaky-clean website (on which the only writings are those ancient, creaky old Premiere items), I'll just accept the piece for publication myself, leave myself a really complimentary voicemail and write an absurdly large check payable to yours truly. Ha, ha, ha.

If you are an aspiring author, you should know that for $90 US, Lulu.com--which was started by Hamilton, Ont., entrepreneur Bob Young--will print off four rolls of toilet paper printed with your most acerbic, or sickeningly impersonal, rejection letters. (Additional rolls cost $12 each.) [Sci-fi author D. Judson] Hindes was the guinea pig for the project, reports the Shreveport Times. Lulu approached him with the idea, asking if he would share some of his rejection letters. Hindes eagerly obliged and forwarded the usual platitudes that begin "Dear Author," and include such noteworthy phrases as "This doesn't quite fit what we're looking for," "Good luck," and "Keep writing!"

Happy Birthday, APR

At the VIP reception beforehand--no, I'm not a VIP, but my pal Mark Stein managed to shoehorn Nina and me inside--a stellar cast of American poets prowled the room: John Ashbery, Robert Pinsky, Jorie Graham, Robert Hass, Rita Dove, Ed Hirsch. A few steps from the bar, clutching my champagne flute like festive prop, I almost failed to recognize Ashbery. He looks less studious without his glasses on, almost jolly, like the village toymaker in a Disney movie. I introduced myself and asked what he thought of Larissa MacFarquhar's recent profile of him in The New Yorker. "That's what everybody keeps asking me," he replied. "You know, I used to have this recurrent dream where I was the only naked person in a crowded room. That's exactly how I feel now."

Not wanting to be yet another media-driven tormentor, I asked him about Laura Riding's poetry. I had recently been reading Other Traditions, and was intrigued by his description of Riding's wretched life and thorny aesthetic: "As may be evident from what I have said so far, Laura Riding was what we would call today a 'control freak.' Her poetry, hedged about with caveats of every sort in the form of admonitory prefaces and postscripts, presents us with something like a minefield; one reads it always with a sensation of sirens and flashing red lights in the background." She was, Ashbery told me, a difficult person. "Many years ago, I sent her a couple of notes," he recalled. "Words of admiration." What he got in return were cantankerous shots across the bow. Ashbery went on to note that he was playing hooky from the National Book Awards ceremony in Manhattan. At this point I began to fear I was monopolizing the great man (no irony there), so I moved off, and heard another person ask him about the New Yorker article. Poor guy.

Nina and I reconvened near the cheese-and-cracker table. From there we could observe Robert Pinsky (grinning that benign alligator's grin) and Robert Hass and--Meryl Streep! The actress had agreed to juice up the proceedings by reading a selection of Emily Dickinson poems. She was wearing a long, white, tunic-like blouse, and her pop-cultural wattage promptly made everybody else in the room look like factory seconds. We watched her greet Jorie Graham with a soulful hug. Then we were all herded toward the stage downstairs, where the readings were to take place. On the way, we passed through a life-size display of bronze figures: the Founding Fathers, debating the Constitution. There was Benjamin Franklin, and John Hancock, and philandering Gouverneur Morris with his wooden leg--supposedly he did most of the actual writing. James Monroe was small. I could have beaten him up. But we couldn't linger, the poets were about to mount the stage.

Ed Hirsch, one of American poetry's great enthusiasts, did the introductions. Ashbery batted first. He read two short pieces from Where Shall I Wander (the same two he had read the previous night at an NBA curtain-raising event): "Ignorance of the Law Is No Excuse" and "Interesting People of Newfoundland." The second one in particular struck me as a signal event: the beginning of Ashbery's Garrison Keillor Phase. There's often an undercurrent of bemused, register-hopping comedy in Ashbery's work. But here he worked wonders with his deadpan delivery: people were laughing, as if poetry might actually give Larry David a run for the money.

Newfoundland is, or was, full of interesting people.Like Ashbery, most of the poets kept things light, or at least celebratory. Dove read three short pieces about Rosa Parks, chocolate, and ballroom dancing, plus a playful prose poem about the many deficiences of prose. Hirsch evinced a similar sweetness--there was one piece about eating cotton candy with his grandfather--and even the more politically charged utterances from Pinksy and Hass had their moments of rhetorical uplift. But Graham, reading from Overlord, was a definitive bummer. I give her credit for dipping into this metaphysical spin on the Normandy Invasion. Still, nothing dampens a party like a poem about a dying cat (from AIDS, no less), and Graham's tortured cadences left a lot of unhappy campers in the audience: "There is no excrement but she is trying to cover it / everywhere. Her claws make a horrible sound on the stone floor as she tries. / No no there is nothing there you have done nothing I say. It is some other /species. The compartment of species-distinction I'm in slides its small door / shut." Luckily Streep delivered a palate-cleanser before dinner. She read with the kind of control and dramatic modulation you seldom hear from poets (it's not their job, after all), and wrapped up with eight ecstatic lines and a look of relief:

Like Larry, who would make a fool of himself on street corners

for a nickel. There was the Russian who called himself

the Grand Duke, and who was said to be a real duke from somewhere,

and the woman who frequently accompanied him on his rounds.

Doc Hanks, the sawbones, was a real good surgeon

when he wasn’t completely drunk, which was most of the time.

When only half drunk he could perform decent cranial surgery.

There was the blind man who never said anything

but produced spectral sounds on a musical saw.

If all the griefs I am to haveAt dinner, I asked the charming Rita Dove whether prose was really as bad as all that. "Oh, no," she said, laughing. "I've written plenty of prose--short stories, criticism, even a novel." Just joshing, then. Next question: what were the primary duties of the Poet Laureate, in which capacity she served from 1993 to 1995? To judge from her answer, the Poet Laureate makes it all up as he or she goes along. Dove dwelled with particular relish on a series of spots she had made for the Lifetime Channel: 30-second bits and bobs of poetry wedged between the usual tearjerking fare (I speak from experience).

Would only come today,

I am so happy I believe

They'd laugh and run away.

If all the joys I am to have

Would only come today,

They could not be so big as this

That happens to me now.

I went back to my roast beef. My final poetic enounter came as the lights were being turned out. I chased down Robert Hass and told him how much I loved his Milosz translations--especially the expansive pleasures of A Treatise on Poetry. "There's another long poem I may try to translate," he told me. "It's called A Treatise on Morality." (Poking around the Web, I see that Traktat moralny first appeared in a Polish magazine in 1948.) Hass also shared an amusing anecdote about Milosz's appearance at a Poetry Flash reading in San Francisco: against that backdrop of ethnic militancy and New Age vapor, the late, great Nobel laureate was evidently something of an odd man out. Still, he read his poem, then returned to his seat next to Hass and inquired: "Did I do good?" Needless to say, he did good.

Thursday, November 10, 2005

Radu, John, Paul, George, and Ringo

I was just listening to Radu Lupu's recording of Brahms's Three Intermezzos, which the ever reliable Alex Ross placed in his "personal pantheon of the most beautiful piano records ever made." What the hell, I bought it. And he was right: Lupu has a gorgeous, melting touch, which seems to erase the piano's essential character as a percussive instrument. I saw him play in Seattle about five years ago--the reclusive performer, with his Transylvanian haircut and beard, insisted on changing pianos halfway through the show--and he topped even his own fluid recording of Schubert's Four Impromptus. (That CD, part of the Decca Legendary Performances series, retails for a meager $11.98. If you don't buy it, you're insane.)

I was just listening to Radu Lupu's recording of Brahms's Three Intermezzos, which the ever reliable Alex Ross placed in his "personal pantheon of the most beautiful piano records ever made." What the hell, I bought it. And he was right: Lupu has a gorgeous, melting touch, which seems to erase the piano's essential character as a percussive instrument. I saw him play in Seattle about five years ago--the reclusive performer, with his Transylvanian haircut and beard, insisted on changing pianos halfway through the show--and he topped even his own fluid recording of Schubert's Four Impromptus. (That CD, part of the Decca Legendary Performances series, retails for a meager $11.98. If you don't buy it, you're insane.)Meanwhile, I concluded my marathon viewing of The Beatles Anthology last night--all eight hours, plus the extra DVD of bonus material. It's not exactly flawless. By the end of the third disc, you feel like you've heard the Fabs singing "Twist and Shout" about 19 times (and you have, you have). There's also the squirm-inducing spectacle of Sir Paul McCartney doing the revisionist thing: Macca can't stop himself, he's always defending his patch of historical turf. That said, I got quite involved--a little teary, even--watching the band decline and fall. No doubt the story pushes some buttons for this child of the Sixties. Dashed hopes, lost youth, receding hairline: it's all there, plus the music, which still makes most of our current fare look pretty pallid.

Wednesday, November 09, 2005

Post-KGB, The Dying Gaul, Fitty

NANCY DREW'S MOTHERS Melanie Rehak reads from her book Girl Sleuth: Nancy Drew and the Women Who Created Her (Harcourt), about the many writers who contributed to the mystery series under the pen name Carolyne Keene. Ms. Rehak is joined by James Marcus, whose latest novel, Amazonia (HarperCollins), is about a team of scientists and American military researchers investigating a medical mystery deep in the jungle.Next: The Dying Gaul, which I saw on Monday night and started to regret about about twenty minutes into the proceedings. I admired Craig Lucas's screenplay for The Secret Lives of Dentists, and the first-time director has rounded up an excellent cast for his pansexual love triangle: Campbell Scott, Peter Sarsgaard, and Patricia Clarkson. But after an effective opening act--Scott, who's matured into an oddly jug-eared leading man, has a wonderful turn as a studio sleazeball--the whole thing devolves into paper-thin theatrics. Clarkson, discovering that Sarsgaard is bonking her husband, seeks revenge. To that end, she makes his (virtual) acquaintance in an online chat room, then tortures him by pretending to be his reincarnated ex-lover. At this point my attention began to wander. So did Sarsgaard's campy diction: couldn't the continuity person tell him he'd been lisping in the previous scene? Oh, well. It's an ambitious film, undermined by a fatal quotient of silliness--The Changing Light at Sandover meets Love, American Style.

Other bulletins: Fifty Cent brings a gigantic entourage to a preview screening of his film, including his grandmother (via the New York Daily News). Yet even Fitty takes pains to protect her tender sensibilities:

Later at the screening, at Loews 19th St.--hosted by GQ editor Jim Nelson, who revealed that Fitty will be a GQ Man of the Year--the rap star sat next to his maternal grandmother. When a graphic, all-nude sex scene with Joy Bryant came on, Fitty leaned over and advised: "Grandma, close your eyes."Such a nice young man! Read the entire, deeply entertaining dispatch here.

Thursday, November 03, 2005

Get a room!

This was no one-night stand. Scientists in India say they have discovered two fossils fused together in sexual union for 65 million years. The findings were published in the October edition of the Indian journal Current Science, which said it was the first time that sexual copulation had been discovered in a fossil state, according to the Press Trust of India news agency.It does open the door for an X-rated version of Hemo the Magnificent, doesn't it? That was no fungus myxomycete--that was my wife! Okay, I'll stop now.

Letter perfect

Last year I translated most of Saul Steinberg's Letters to Aldo Buzzi, an epistolary treasure trove covering the years from 1945 to 1999. Steinberg met Buzzi during the 1930s in Milan, where they were both attending architecture school. Neither went on to become an architect. Steinberg, a Romanian Jew, fled Milan in the face of Italy's increasingly suffocating "racial laws," briefly cooled his heels in Santo Domingo, then made landfall in the United States in 1942. Buzzi, meanwhile, embarked on a long career as jack-of-all-trades: editor, screenwriter, publisher, and author (of such Epicurean productions as Journey to the Land of the Flies and The Perfect Egg.) The Letters, originally published in Italian by Adelphi, and only after much agonized hesitation by Steinberg, are a one-sided affair--ie, no letters from Buzzi. This seems like a shame. Perhaps at some point this wonderful writer (he's the one on the right, looking very glamorous and Italianate) will allow a culling of his own letters to see print. Meanwhile, the book is a treat. Also, the most intimate glimpse we'll ever get of the enigmatic artist, who will be the subject of a major show at the Morgan Library in 2006.

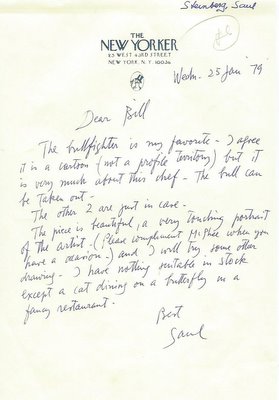

Last year I translated most of Saul Steinberg's Letters to Aldo Buzzi, an epistolary treasure trove covering the years from 1945 to 1999. Steinberg met Buzzi during the 1930s in Milan, where they were both attending architecture school. Neither went on to become an architect. Steinberg, a Romanian Jew, fled Milan in the face of Italy's increasingly suffocating "racial laws," briefly cooled his heels in Santo Domingo, then made landfall in the United States in 1942. Buzzi, meanwhile, embarked on a long career as jack-of-all-trades: editor, screenwriter, publisher, and author (of such Epicurean productions as Journey to the Land of the Flies and The Perfect Egg.) The Letters, originally published in Italian by Adelphi, and only after much agonized hesitation by Steinberg, are a one-sided affair--ie, no letters from Buzzi. This seems like a shame. Perhaps at some point this wonderful writer (he's the one on the right, looking very glamorous and Italianate) will allow a culling of his own letters to see print. Meanwhile, the book is a treat. Also, the most intimate glimpse we'll ever get of the enigmatic artist, who will be the subject of a major show at the Morgan Library in 2006. Anyway, I mention all this by way of crowing over a purchase I made on eBay: a short letter from Steinberg to William Shawn. I came across the listing almost by chance, and after a mild-mannered bidding war, got the piece for a song. As you can see here, Steinberg is discussing potential art for a New Yorker article. If I weren't so intimidated by my copy of The Complete New Yorker--so far I'm too overwhelmed even to remove the shrinkwrap--I would do some quick investigation and figure out which article in particular. (Well, there's always tomorrow.) In the meantime, I'm studying the artist's handwriting, the upward slant of the sentences and the distinctive S. I'm also wondering how this letter--uncreased, so I assume it traveled by interoffice mail--escaped the New Yorker archives and slithered into the private sector. Perhaps it was discarded. Or never sent. I don't like to make a fetish out of these things, but I admit I'm delighted to own it.

Anyway, I mention all this by way of crowing over a purchase I made on eBay: a short letter from Steinberg to William Shawn. I came across the listing almost by chance, and after a mild-mannered bidding war, got the piece for a song. As you can see here, Steinberg is discussing potential art for a New Yorker article. If I weren't so intimidated by my copy of The Complete New Yorker--so far I'm too overwhelmed even to remove the shrinkwrap--I would do some quick investigation and figure out which article in particular. (Well, there's always tomorrow.) In the meantime, I'm studying the artist's handwriting, the upward slant of the sentences and the distinctive S. I'm also wondering how this letter--uncreased, so I assume it traveled by interoffice mail--escaped the New Yorker archives and slithered into the private sector. Perhaps it was discarded. Or never sent. I don't like to make a fetish out of these things, but I admit I'm delighted to own it.SPECIAL UPDATE: Sheila Schwartz at the Saul Steinberg Foundation was nice enough to run down the reference in Steinberg's letter. He was referring to John McPhee's profile of a nameless, superlative chef, "Brigade de Cuisine," which ran in the February 19, 1979 issue of The New Yorker. Ye gods, I recall reading the original article in the library at Wesleyan. It was subsequently reprinted in Giving Good Weight.

Labels: Aldo Buzzi, Saul Steinberg, William Shawn